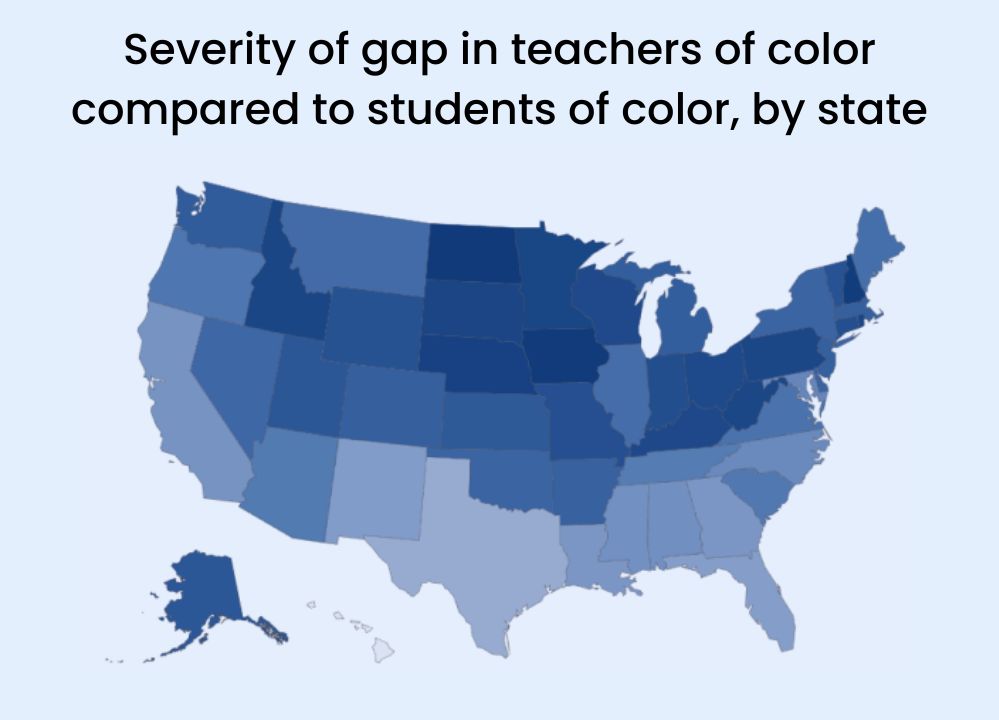

Darker = More Severe. Image via the74million.org

Attracting diverse teachers is of critical importance for students of color across a range of metrics — improved achievement, higher rates of attending college, lower suspension rates, and so on. But the actual “state of the states” is fairly dire. Every state and the District of Columbia has a deficit in this area: more students of color than teachers of color. In the graphic at right, the darker the shade of blue, the bigger the gap is. Even this doesn’t really show the scale of the problem. For example, in Maine, 4% of public school teachers identify as people of color and 13% of public K-12 students identify as people of color. While the percentage point gap is -9 percentage points, the relative gap is 66.2%6 (because there are so many more students than teachers overall), meaning Maine has three times more students of color than teachers of color. As The 74 Million points out, places like this often have a less diverse workforce to begin with so the challenge of bringing the diversity of teachers in line with the diversity of students is that much greater.*

We already know that enrollment in traditional teaching programs has been on the decline for several reasons, but the expense of the degree coupled with a low rate of financial compensation is a major factor. Most states saw declines in all enrollees, with the exception of Texas, Washington state, Alabama, New Mexico, and the District of Columbia — and their increases (particularly Texas’) were due to alternative certification programs.** Enrollees in alternative programs are also more likely to complete the program than are those in traditional programs.**% While this might make it seem like alternative programs are the way of the future, it’s important to note that alternatively-certified teachers leave education in higher numbers than those who complete traditional programs, mainly due to a lack of professional support. But understanding why these programs are more successful is important:

It’s money.

This is the logical conclusion that researchers and federal and state data crunchers keep arriving at, over and over again:

- Why do Grow Your Own programs work? Money. “GYO programs have traditionally found success in…offering financial aid… [and] reducing financial barriers.”

- What did 5 successful districts say worked to increase their pool of available and diverse educators? Money. “Each district leader emphasized that committed leaders can build buy-in across the district and direct resources to support workforce diversity efforts” (‘direct resources’ is code for giving money).

- What’s a major bar to taking public service jobs with low pay like teaching? Money. “Research indicates that undergraduate students were less likely to choose public interest jobs with lower pay, particularly in education, when they had student loan debt. With higher student loan debt, students are more likely to pursue careers with higher pay. This means that to increase the racial diversity of the U.S. teaching workforce, interventions focused on reducing debt, particularly for students of color, may be effective.” How do we reduce debt? Money.

- Here’s an interesting idea: “Rather than waiting to begin recruiting teachers of color at the college level, some districts are encouraging middle and high schoolers to explore teaching careers. The Center for Black Educator Development, for example, partners with districts to create high school teacher academies that offer prospective educators a three-year curriculum centered on the Black experience. In Philadelphia, that means high school juniors and seniors can take college courses and graduate with an associate degree in education along with a diploma.” This is basically a free (no money) associates degree.

image via nctq.org

Let’s circle back to loan forgiveness because it’s a biggie. EdWeek reported that “teachers of color are more likely to take out loans—and more of them—than their white peers. On average, Black educators had an initial total of $68,300 in loans, compared to $54,300 for white educators and $56,400 for Hispanic educators.” I think it’s fair to extrapolate that students of color overall probably have more and larger loans than white students, so it becomes more risky to take a job than might not enable you to pay what you owe, or that might keep you owing for a long time and jeopardize your ability to pay for housing or transportation or child care. EdWeek further noted that in surveys, teachers of color cited the following pay-related strategies to attract and retain diverse educators:

- Expand load forgiveness and/or service scholarships (58 percent of teachers of color—and 67 percent of Black teachers);

- Create teacher residencies, which allow trainees to spend up to a year student-teaching and earning a paycheck while completing coursework (31 percent of teachers of color);

- Increase teacher salaries throughout the pay scale (72 percent of teachers of color), and

- Offer higher starting salaries (45 percent).

When you go right to the source and ask what incentives would make it easier to choose education and stay in it, the answer is money. Interestingly, when asked about bonuses, such as signing bonuses, educators of color indicated these weren’t as effective unless they were higher than $5000. In other words, the money needed to be substantial to have an effect.

And one more shout out for money: Teachers of color are both more likely than their white counterparts to work in schools that struggle to attract and retain top talent, and more likely to serve large numbers of students who look like them and benefit most from more diverse staff. A RAND Corp. study found that higher pay reduced teacher attrition overall and the effect was greatest in urban schools (where teachers of color are most likely to work). In fact, the study found that for every $1,000 increase in pay for teachers working in these schools, attrition fell by 6%. While this isn’t specific to teachers of color, offering more money to teach in more challenging schools mitigates against a lot of problems those schools encounter, like attracting and keeping staff.****

In short, if we want to see more teachers of any kind, but especially more diverse teachers to help reach and effectively educate children of color, we have to be willing to commit funds to the process. States that aren’t willing to fund these kinds of programs and incentives are demonstrating in the clearest terms where their priorities lie.

_____________________________________________________________

*If you want some actual numbers, here is the Pew Research Data on Teacher Diversity vs. Student Diversity.

**Texas has a huge, privately managed, for-profit alternative certification program called Texas Teachers of Tomorrow. The Texas Education Agency (TEA) has recommended revoking the company’s accreditation, because they say it has fallen short of standards. A judge has granted the company a temporary injunction that prevents state education officials from moving forward. The company now has until June of 2024 to prove it is capable of producing adequately certified teachers. These for-profit companies are popping up in lots of places, particularly where teacher staffing shortages are most severe. They definitely bear watching.

***Some of these declines are trending upward since 2019.

****The Rand Corp. report is fascinating. There’s an interesting description of which states are explicitly using financial incentives to attract or retain teachers of color or those working in hard-to-staff schools. Weirdly, Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio, and Pennsylvania have created programs to provide additional pay or other incentives for hard-to-staff schools, but they don’t fund them. Kind of hard to see the point in that, but there we are.