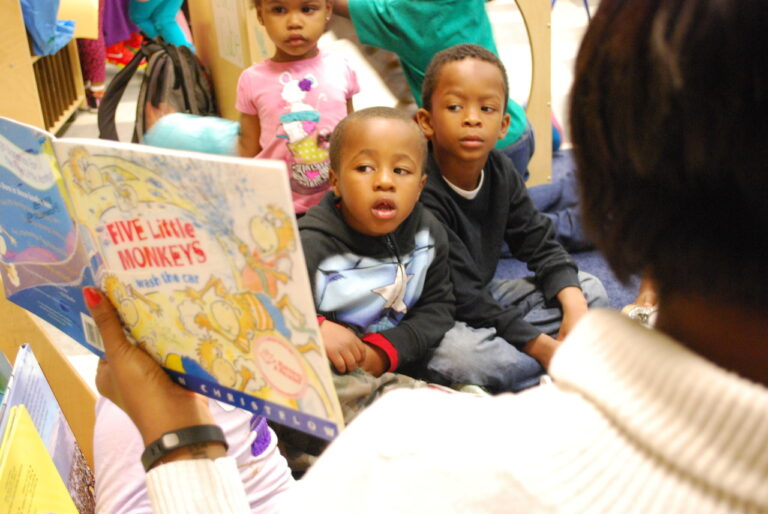

image via preschool_partners.org

In 1971, a critical (but perhaps not much noted at the time) shift occurred in the U.S.. In that year, President Nixon vetoed a plan that would have provided universal child care and accompanying preschool for all children. The demise of that plan resulted in a sort of de facto belief that most preschool should be paid for privately. Rather than build a national, comprehensive (and expensive) system of preschool education open to all children, public money would sensibly be targeted toward preschool for poor children who clearly “needed” it. Forty-two years later, a study published in the Journal of Human Resources is refuting this thinking, finding that preschool programs reserved for poor children just aren’t as effective as universal ones that include children from all income levels.

There is a certain logic to the idea of targeted preschool programs. A 2013 study of Georgia and Oklahoma preschoolers in universal programs found that the programs had a significant, positive effect for disadvantaged children but no effect on children from high-income families.* These are the kids whose parents would have enrolled them in private preschool had there not been a publicly-funded option. For those families, the program was a financial windfall rather than their only means to access early childhood education. Since there was no benefit, thought some researchers, why not offer preschool only to the poor kids who need it most? It should be win-win: the kids get the critical skills and the state saves some money. But in the most counter-intuitive way possible, this turned out not to be the case.

image via americanprogress.org

In this most recent study, researchers looked at survey data from the National Early Childhood Longitudinal Study and compared the test scores of thousands of 4-year-olds from more than 30 states. Some of these states offered targeted state preschool programs, some offered universal state preschool open to all income levels, and some offered no state-funded preschool at all. They found that low-income children who enrolled in state funded, universal preschool had far better reading test score gains than children in states with programs targeted to poor children. There was a smaller effect for math scores as well for disadvantaged children in universal preschool programs.**

Why this is true wasn’t really part of the study, but researchers made some guesses:

- A universal program may focus more on kindergarten readiness rather than on remediating skills poor children are deemed to be lacking. ***

- Higher income families generally have more social capital and possibly a heightened sense of entitlement, which could prompt them to hold programs more accountable. They expect more from the program and will speak up if they don’t see it.

- Mixed-economic preschool may be creating a “peer effect,” where children learn as much from each other as they do the teachers. The presence of children with more access to learning experiences outside of school provides another, critical learning arena for low-income children.

And I’m going to add one of my own: studies have demonstrated that targeted preschool programs look very different from those that higher-income families want (and pay) for their children to experience. These private programs look much more like gifted and talented programs with lots of agency for the child to choose activities that interest them, and learning that is organically integrated into hands-on, experiential play. Targeted programs, however, tend to look more like drill-and-kill, with teacher-directed, rote activities like counting and alphabet practice. Children in these programs are more likely to do worksheets and even sit through teacher lecture. It’s both fair and accurate to say that comparing these two types of programs is trying to compare apples to oranges — or maybe apples to horned melons. They are vastly different in design, expectation, and delivery.

image via edsource.com

Here’s the really interesting bit: The Journal of Human Resources is a microeconomics journal, not an education one; their primary focus was on the financial feasibility and return on investment in publicly funded preschool programs. In other words, which program is the most cost effective in the long run? If you guessed “targeted preschool” you’d be wrong. Universal programs cost more overall because they serve more children, but their return on investment on every dollar spent is much, much greater. The other interesting thing here is that this practice appears to be neutral for higher-income children; their test scores are what they would have been had they attended a private preschool. They aren’t being sacrificed on the altar of another child’s need; rather, their presence in the preschool program appears to be a key factor in leveling the playing field.

Their conclusion? To reap the greatest positive benefit of preschool for disadvantaged children, the state also needs to pay for the kids who aren’t disadvantaged. It’s a false — and detrimental — economy to do otherwise.

___________________________________________________________________

*I feel bound to mention here that studies are deliberately narrowly construed; researchers are comparing specific effects. As a result, one study can find that targeted preschool has a positive effect for low-income children and another can find that it doesn’t have a long term positive effect and both statements can be true. It matters very much what kinds of programs were included in the study, the demographics of the students, and the timeframe the researchers were analyzing. Changing those variables can (and does) change the conclusion of one study compared to another. This seems contradictory, but because they are looking at specific slivers of data and different groups and timeframes, it’s not.

**This held true even when researchers adjusted for class size, spending per pupil, and teacher training and education in the state programs, as well as children’s alternate care arrangements.

***A similar conclusion was reached by researchers at Vanderbilt University looking at a targeted preschool program for poor children in Tennessee. They found that although the program led to initial gains, these evaporated quickly and children were both more likely to be in special education and more likely to be suspended as they moved up the grades than disadvantaged children who were not in the targeted program. Ouch.