Last time, we discussed the fundamental problem of disparities in suspension and expulsion rates for children of color and how this phenomenon begins at the very first point of contact for many children: preschool. Disproportionate suspension and expulsion for children of color continues as they move up the grades. We would expect that children would be suspended at rates commensurate with their enrollment percentages — so if 15% of the student population is Black, around 15% of all suspensions should be Black students, etc. But the data show otherwise. In 2016-17, Black students made up 15% of K-12 public school enrollment, but they accounted for almost 40% of students who were suspended, expelled, or arrested. Students with disabilities are in a similar situation; they, too, comprise 15% of the total student population but about 37% of all suspensions and expulsions. The reverse is true for white students: although they made up more than 45% of enrollment, they were suspended at lower rates — only around 33% of all suspensions. This is still a high number but not as high as we would expect. This is recent, but not new, data — this pattern has been playing out, again and again, for decades.

Last time, we discussed the fundamental problem of disparities in suspension and expulsion rates for children of color and how this phenomenon begins at the very first point of contact for many children: preschool. Disproportionate suspension and expulsion for children of color continues as they move up the grades. We would expect that children would be suspended at rates commensurate with their enrollment percentages — so if 15% of the student population is Black, around 15% of all suspensions should be Black students, etc. But the data show otherwise. In 2016-17, Black students made up 15% of K-12 public school enrollment, but they accounted for almost 40% of students who were suspended, expelled, or arrested. Students with disabilities are in a similar situation; they, too, comprise 15% of the total student population but about 37% of all suspensions and expulsions. The reverse is true for white students: although they made up more than 45% of enrollment, they were suspended at lower rates — only around 33% of all suspensions. This is still a high number but not as high as we would expect. This is recent, but not new, data — this pattern has been playing out, again and again, for decades.

Enter the Brown Center Study: Because of a study in North Carolina that found Black students assigned to Black teachers experienced reduced rates of suspension, the Brown Center for Public Policy conducted its own study that examined data from the New York Public Schools to see if those same effects could be detected in a large, urban population and whether there might be similar effects for non-Black children of color. The scale was large — 10 years worth of data (2007 to 2017) on teacher placement in grades 4-8 in a district that serves 1.1 million students. The scale of the project is important because a sample that size makes their findings more reliable and replicable. Here’s what they found:

All three racial groups—Black, Latino, and Asian American—showed negative associations between exposure to same-race teachers and suspensions. In years that students in grades 4-8 were assigned more same-race teachers, they were less likely to be suspended from school, compared to years in which they were assigned fewer same-race teachers. Black students showed the largest association, but the effects were statistically significant for Latino students, and of similar magnitude (although only marginally significant) for Asian American students. This is important, as prior studies have found this relationship among Black students only, but our work suggests this race-match benefit is not unique to Black students. (emphasis mine)

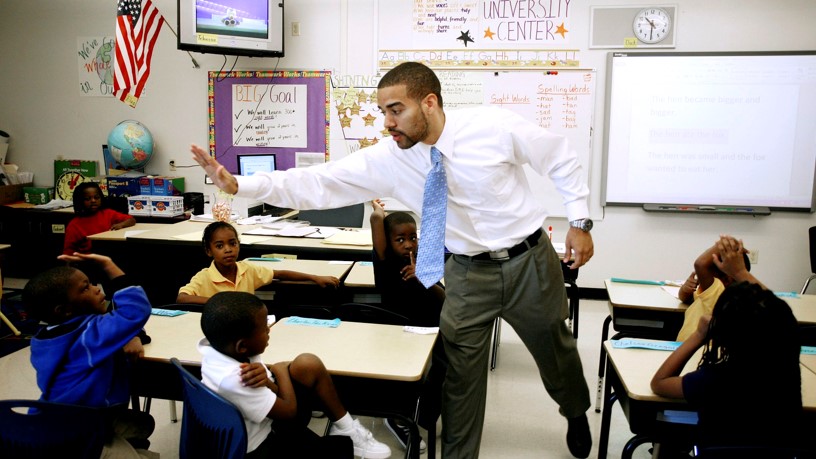

image via The Atlantic

Let’s be sure we have this clear: when children of color were assigned to teachers of their same race (or to more teachers of the same race for grade levels where students had multiple teachers), the likelihood of being suspended that year went down (the ‘negative effect’).

Then — and I just love this — they conducted a little thought experiment. What would have happened if the number of same-race teachers a student was assigned to had been increased by 1 standard deviation? The result of that increase was a 3% decrease in suspensions. That doesn’t seem like much, but in a district with so many children over a ten year period, it translated to:

- 230 fewer instances of suspension for Asian American students,

- 1,600 fewer suspensions for Latino students, and

- 1,800 fewer suspensions for Black students over that period.

And, since the median length of suspensions was 5 days for Black and Latino students and 3 days for Asian American students, this translated to:

- 680 more days in school for Asian students in grades 4-8,

- 8,000 additional days in school for Latino students, and

- 9,000 additional days in school for Black students over the 10-year period.

This is the fundamental equation: suspension from school = days of instruction lost. We’ve discussed this vicious cycle before where a child acts out, is sent out of the classroom, misses instruction, comes back, is lost, acts out, gets sent out of the classroom, lather, rinse, repeat. Having a same-race teacher breaks the pattern for children of color and results in more days in class, learning. This effect was biggest on boys, but present in girls as well, though to a lesser degree.

There is already a robust body of research that demonstrates multiple benefits for students of color when districts undertake ethno-racial matching between students and teachers. These include: better academic performance, higher high school graduation rates, higher likelihood of attending college, among others. Brown Center’s research is one more layer of benefit to this practice and a strong argument for increasing efforts to recruit, fund, place, and retain teachers of color with students who will benefit from their presence public classrooms.

Here’s my little thought experiment: what if we could go back in time and match teachers of color with students of color in preschool? How many more days of instruction (and socialization, and experimentation, and exploration) would those children have under their belts before they entered Kindergarten? And what if we could match them all the way up the grades — what effect might that have on their attendance, their behavior, their achievement? Brown Center’s research tells us the answer.

Representation matters.