image via nwea.org

In the last post, I discussed Mississippi’s “miracle” of improved literacy and one of the tent poles of that program: grade level retention. Mississippi isn’t alone in this type of policy: at least 25 states either allow or require retention when a child fails to pass a reading test at the end of 3rd grade. The prevalence of these policies demands a hard look at whether repeating 3rd grade improves literacy and whether any benefit also comes with negative effects. Spoiler: even a cursory look at the available data on retention on its own indicates that it doesn’t deliver on its promises. A deeper look shows that in the long run, it does more harm than good.

A 2001 meta-analysis from UC Santa Barbara1 found that all 20 of the studies it reviewed “fail[ed] to demonstrate that grade retention provides greater benefits to students with academic or adjustment difficulties than does promotion to the next grade.” That meta-analysis went on to call for “researchers, educational professionals, and legislators to abandon the debate regarding social promotion and grade retention in favor of a more productive course of action in the new millennium.” A 2019 study of South Carolina’s retention program found only short term academic gains that faded fairly quickly.2 One study published in Florida (which has a retention policy) was initially touted as proof that retention works. This 2017 analysis of student outcomes under the retention system found that kids who were retained had big initial gains in achievement.3 But (and it’s a big but) within five years, the score increases faded out, and these students weren’t doing any better than their same-age peers. That study did find that students who were retained had higher grade point averages and took fewer remedial courses in high school than students who had similar reading abilities but weren’t held back. However, that finding comes with some big confounders; students who were retained were given several extra supports that they didn’t have before retention, like a state-required reading support plan for each retained student, extra time for reading, and – this one is crucial – placement with effective teachers. This begs the question of why students weren’t given those supports before grade 3. Highly relevant to this is a University of North Carolina study from 2018 that examined North Carolina’s retention policy – a policy that didn’t require any intervention beyond simply retaining poor readers. That study found that retention on its own, without any differentiated intervention for those retained, had no effect on student achievement.4

In addition to its highly-debatable success record, retention for any reason is harmful across a range of metrics, starting with big disparities in who gets retained. Nationally, Black students are retained at twice the rate of White students, and in some areas their rate of retention is even higher (In Mississippi, for example, 71% of all retained students are Black). Poor students are also retained at double the rate of their wealthier peers. A study of Michigan’s now-defunct retention policy concluded that higher income students were able to circumvent retention policies more easily than other students, leading to those big racial and economic disparities. Additionally, where a student attends school affects retention rates: low-performing, urban, and charter schools are more likely to retain all of their retention-eligible students.

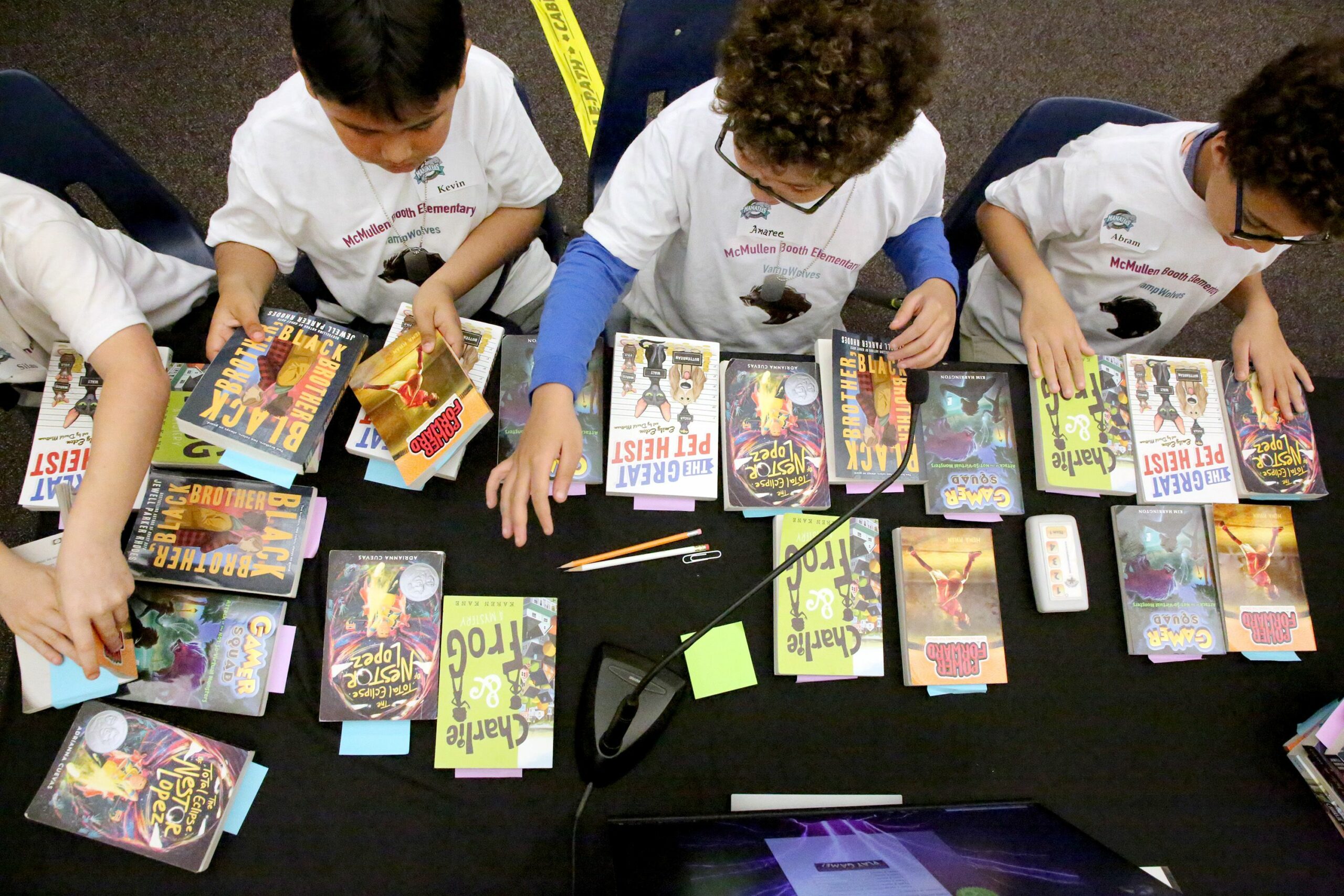

image via tampabaytimes.com

All of this is important because of the measurable academic harms retention creates for kids. One recent study found that being held back in the elementary grades increases the odds of dropping out of high school, and that these effects were strongest for Black and Latinx girls.5 In the 2001 UC Santa Barbara meta-analysis, many of the studies examined showed that students who were retained had worse academic achievement and social-emotional outcomes than students who were not retained. There is also evidence that students who are retained are more likely to be suspended and more likely to either be bullied or become bullies themselves.6 Further evidence demonstrated a kind of retention feedback loop: the more teachers and principals tended to retain students, the more they believed retention led to improved literacy, and the stronger this belief, the more likely they were to retain eligible students. This type of thinking may be what leads to states like Mississippi retaining almost a full third of their students at least once before they reach grade 4. It’s highly possible that some have been retained more than once, though Mississippi doesn’t report those numbers. It’s important to connect the dots here: since poor kids and Black/brown kids are held back the most, they are disproportionately experiencing the harms inherent in retention practices while simultaneously continuing to experience all the difficulties and deficits associated with the substandard literacy the retention was supposed to remedy. There’s just no way to put a positive spin on what seems like a deliberate decision to ignore hard data.

There is a better way.

Ample research shows that experienced, effective teachers have a tremendous impact on student achievement. Making sure struggling readers are placed with effective teachers is absolutely critical. Struggling readers need early, intensive intervention with targeted instruction. Waiting until students fail the 3rd grade test means we’re intervening after kids are already in jeopardy. More time spent on reading instruction coupled with a high quality classroom environment was directly linked to progress in reading skills.7 More reading improves reading: Research has found that only the time spent actively reading and decoding results in improvement. This means that all the ancillary activities around reading (like grammar instruction) don’t actually result in improved reading. Explicit phonics instruction and comprehension work are most effective. The no-phonics methods of teaching reading have been shown to be ineffective for many students. However, only phonics without making meaning leads to students who can decode at high levels but can’t explain (or retain) what they’ve read. It’s like being able to pronounce words in a foreign language without understanding what they mean. A fusion of both phonics and making meaning is critical.

There’s also a very real way in which the 3rd grade reading test weirdly places the burden of reading on the child — “you failed the test, so you are being held back.” But none of the things listed above are within a child’s span of control. They have no agency in which teacher they are assigned to, what curriculum they are given, how long their teacher elects to spend on reading, how the teacher or system responds to kids who are struggling, and so on. They also have no way of assessing a teacher’s effectiveness — if their teacher isn’t very good at his or her job, how would a kid even know? They’re kids, and the adults charged with delivering learning to them are failing them at every turn. One journalist for the New York Times said the 3rd Grade Gate “lit a fire” under teachers to make sure their students could pass the test. However, I have to point out that even with that impetus Mississippi still retains just over 9% of its students at the end of grade 3, the highest retention rate in the U.S. by a decent margin (Oklahoma is next highest at 6%). In a culture of retention, that “fire” isn’t very effective.

Madeline Hunter’s most famous quote seems sadly apropos here: “If a student didn’t learn, a teacher didn’t teach.”

__________________________________

¹ Shane R. Jimerson (2001) Meta-analysis of Grade Retention Research: Implications for Practice in the 21st Century, School Psychology Review, 30:3, 420-437.

² Jennifer Barret-Tatum, Kristen, Ashworth, & David Scales. (2019). Gateway Literacy Retention Policies: Perspectives and Implications from the Field. International Journal of Education Policy & Leadership 15(10).

³ Guido Schwerdt, Martin R. West, Marcus A. Winters, The effects of test-based retention on student outcomes over time: Regression discontinuity evidence from Florida, Journal of Public Economics, Volume 152, 2017, Pages 154-169

4 Sara Weiss and D. T. Stallings (2018) Is Read to Achieve Making the Grade? North Carolina State University. https://www.fi.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/RtA2018Reportv5.pdf

5 Hughes, J. N., West, S. G., Kim, H., & Bauer, S. S. (2018). Effect of early grade retention on school completion: A prospective study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(7), 974–991.

6 Laura M. Crothers, et al. (2010) A Preliminary Study of Bully and Victim Behavior in Old-for-Grade Students: Another Potential Hidden Cost of Grade Retention or Delayed School Entry, Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26:4, 327-338

7 Barbara M. Taylor; P. David Pearson; Kathleen Clark; Sharon Walpole. Effective Schools and Accomplished Teachers: Lessons about Primary-Grade Reading Instruction in Low-Income Schools. The Elementary School Journal, Vol. 101, No. 2. (Nov.2000), pp. 121-165.