image via abc.com

The NWEA just published a study detailing student progress in 2022-23, creatively titled Education’s Long Covid. Why the report earned that title is clear from page 1: the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are still reverberating throughout the U.S. educational system, even though the pandemic itself is no longer a national emergency.

The report details three key findings for the 2022-23 MAP test results:

- In nearly all grades, achievement gains during 2022–23 fell short of pre-pandemic trends, which stalled progress toward pandemic recovery.*

- Significant achievement gaps persist at the end of 2022–23, and the average student

will need the equivalent of 4.1 additional months of schooling to catch up in reading

and 4.5 months in math. - Comparing across race/ethnicity groups, achievement gains for all students

lagged pre-pandemic trends in 2022–23. Marginalized students remain the

furthest from recovery.

The report is explicitly comparing pre-COVID and post-COVID achievement so “achievement gaps” here means the difference between the pre/post-COVID samples in a particular grade level. When the report talks about gaps between demographic groups, it uses the term “achievement disparities.”

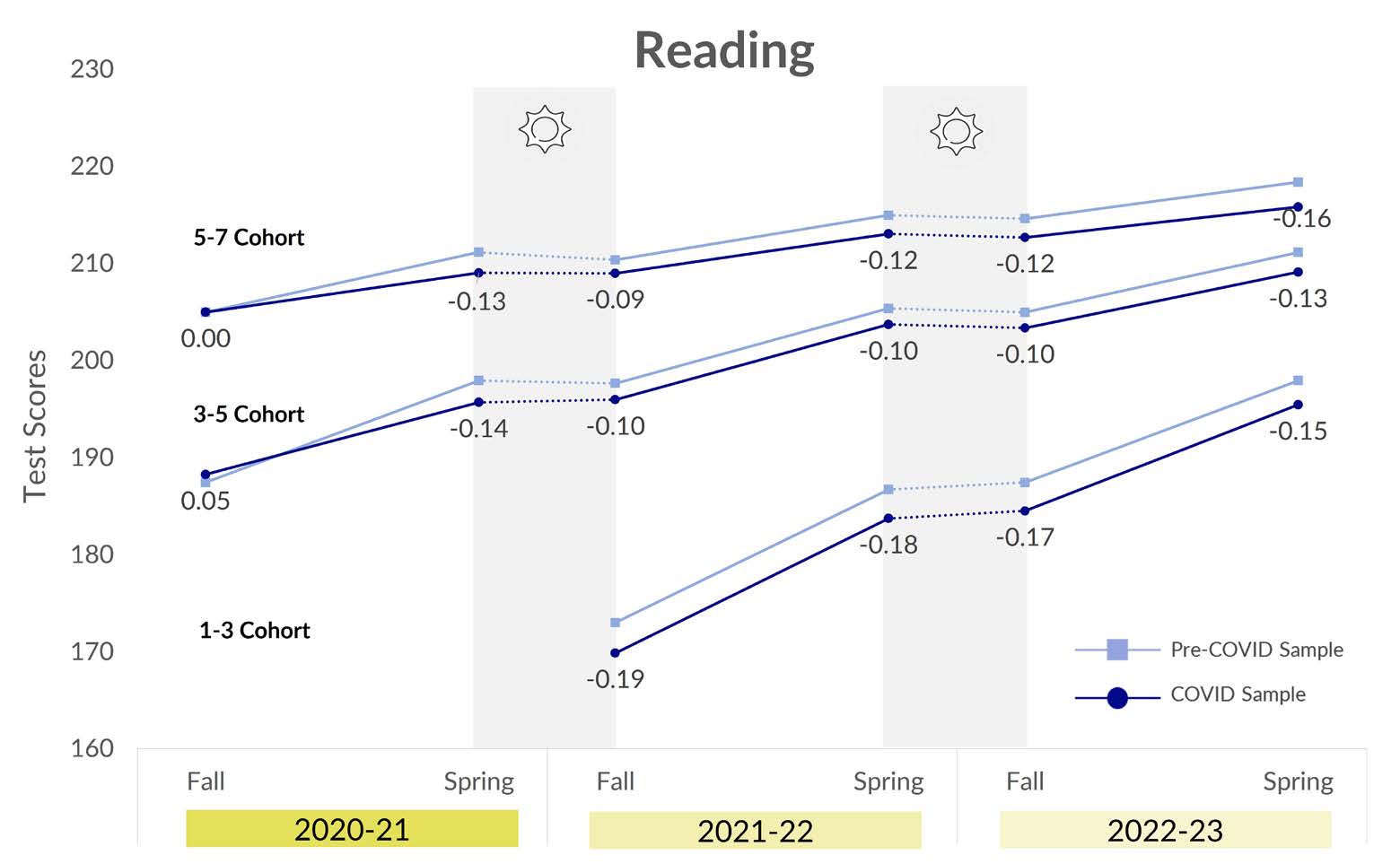

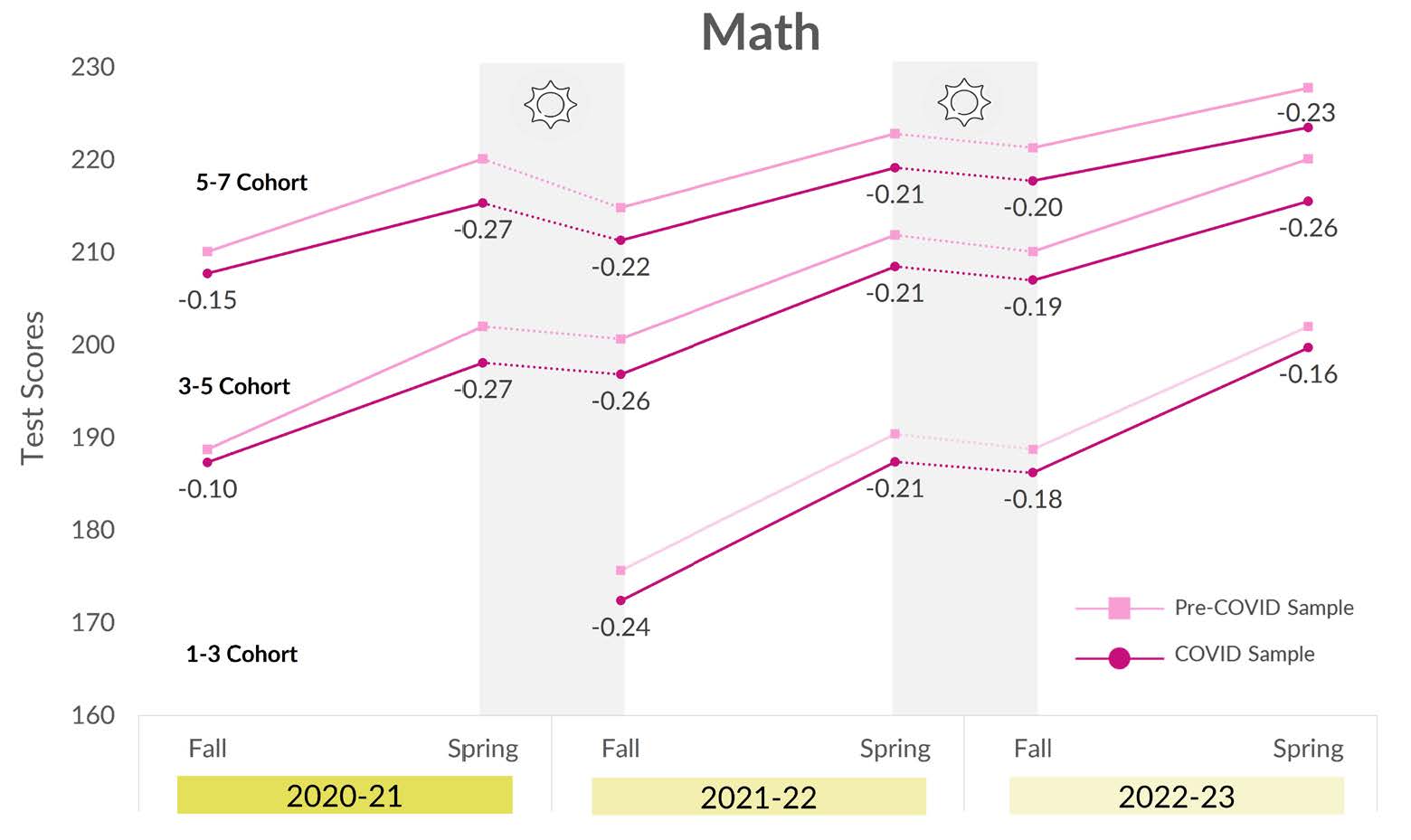

The following graphs show the gaps between expected average growth versus actual growth, pre and post COVID, for Reading and Math (these and all following images via NWEA.org).

These were cohort studies, following the same group of students over a period of 3 school years, with the exception of the youngest cohort which was followed for 2 years but over 4 administrations of the test. Probably the most striking thing here is that for 4 of the cohorts — 5-7 and 3-5 in reading and 5-7 and 3-5 in math, the gaps grew between the 2022 and 2023 assessments, which may be an indication that deficits in learning are compounding over time. Only the youngest cohort appears to be making consistent progress toward pre-pandemic achievement levels. It’s also noteworthy that the gaps were greater in math than in reading.The report concluded that “at the end of the 2022–23 school year, across all grade levels, the average student will require the equivalent of 4.1 months of additional schooling to catch up to pre-COVID levels in reading and 4.5 months in math,” based on pre-pandemic rates of learning. In other words, kids are about half a school year behind where they should be since the pandemic.

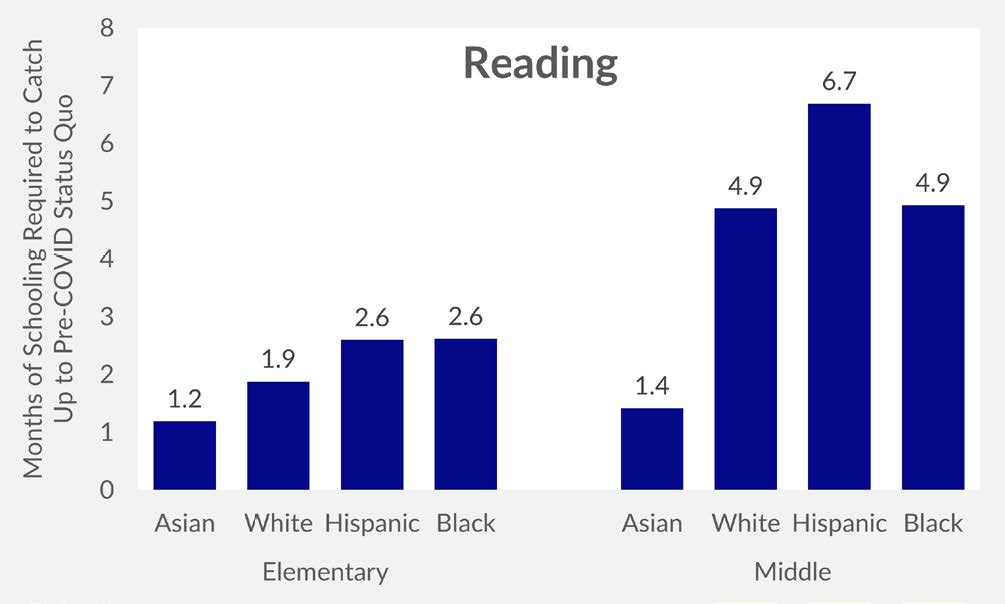

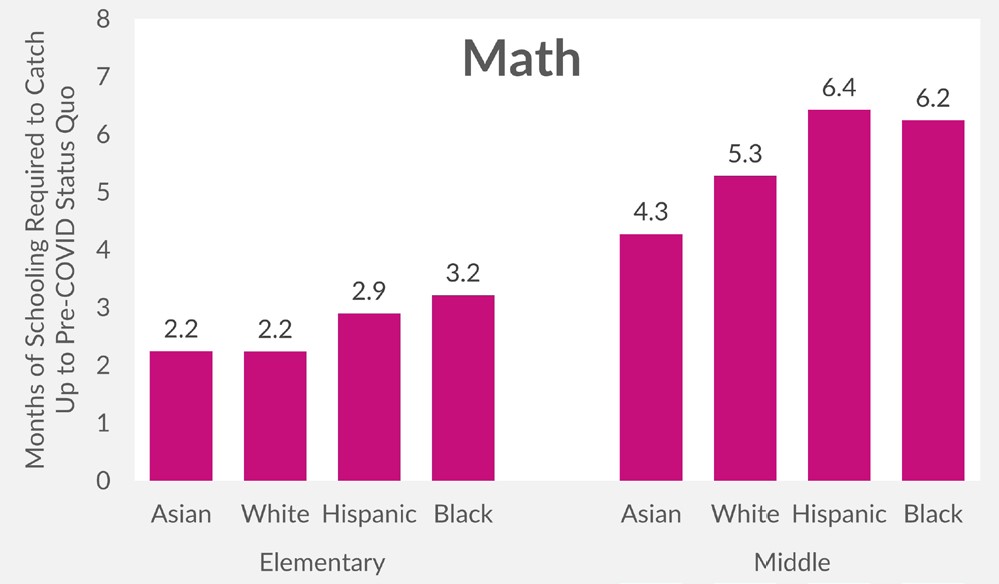

But that figure — 4+ months — is truly an average. The picture changes significantly when we look at the demographic groups.

These data reveal that the extra schooling needed for recovery is higher across groups for middle schoolers and lower for elementary (the reason for this is that elementary students tend to make bigger gains at a faster rate than older kids; yet another reason schools should be intervening early and aggressively when gaps of any kind are smaller). In reading, Hispanic middle school students need almost 7 additional months of instruction — nearly a full school year — to get back to pre-pandemic levels. In math, Black and Hispanic middle school students need a little over 6 months of extra instruction to return to pre-COVID levels.** Of course, all this assumes that teachers will use both existing and extra instructional time as efficiently as possible AND that instruction is focused on acceleration rather than remediation to insure everyone gets up to grade level, and those are very big assumptions.

I like to imagine a group of Hurricane Katrina researchers sitting in a faculty breakroom somewhere, nodding their heads and saying “I told you so.” Nearly all of this was predictable, knowing what we already know about educational recovery after an environmental disaster. Research from Katrina (during which kids missed an average of 7 weeks of school) demonstrated that recovery is a much longer road than anyone anticipates*** and, just as the new NWEA report points out, that the road is longer still for historically marginalized students. More than that, all those extra months of schooling would only get students to the pre-pandemic status quo; they won’t do anything to address pre-existing achievement disparities between demographic groups. NWEA appropriately frames this as a “mounting educational debt owed to marginalized students, who have been most deprived of educational opportunities.”

The report is quick to recognize that schools and teachers have gone to great lengths to try to ameliorate the harms caused by the pandemic and that had they not done so, progress would likely be far worse than it is. But going forward, how we respond to these students with money, resources, placement with effective teachers, and targeted acceleration to get them up to grade level is going to be critically important to their academic success and to their adult opportunities. Or as NWEA put it:

[What] we see at the end of 2022–23 makes it increasingly clear that the scale of the crisis and its repercussions on students’ academic progress surpass what can be fully addressed with the current response. While schools are taking steps in the right direction, the reality is that the depth and breadth of the crisis demands an even more comprehensive, intensive, and sustainable approach if we are to truly mitigate the long-lasting impacts of the pandemic on students.

Many, many students still have a long way to go and we need to pull out all the stops to make sure all of them get there, especially those hardest hit. But with ESSER funds expiring this year and many districts mired in side brawls over books and other distractions, our ability to do that is no sure thing.

*The report uses two terms: recovery and rebounding. Rebounding is a return to pre-pandemic levels or better and is considered “progress toward recovery.” While NWEA doesn’t explicitly define recovery in the report, their wording implies that the rebounding must be consistent for multiple years to be considered recovery. While student progress has rebounded, it has yet to attain pre-pandemic levels and it is not showing consistent progress toward those levels, especially for marginalized students.

**I’m not sure why NWEA didn’t include economically disadvantaged students in the 2023 findings; in previous reports they explicitly addressed achievement for high poverty schools, so we know they have the data.

***Research from Katrina also revealed that learning loss was greater in math than in reading; another parallel replicated by the pandemic.