image via contemplativestudies.org

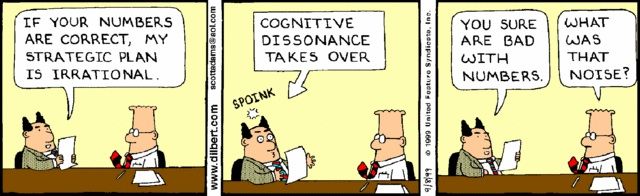

Cognitive dissonance is when a belief , behavior, or attitude is challenged by new information that then forces a person to hold two conflicting positions simultaneously. The necessity of holding two opposing positions at the same time produces considerable stress (or anxiety, anger, guilt, shame, frustration). Sometimes, the dissonance isn’t specific beliefs but rather, the clash of how you think something should or will be versus how it actually is. Culture shock — visiting another country and being overwhelmed with new and different sights, sounds, smells, etc. — is a type of cognitive dissonance. The brain seeks to alleviate the tension this generates. It may do this in different ways: 1) Rejecting the new information as untrue, 2) Rationalizing the old information in some way, 3) Hiding beliefs from others, 4) Admitting only information that confirms the challenged belief as true (confirmation bias), or 5) Shutting down completely. The degree of tension experienced and the ways in which the person seeks to reconcile it depend on how great the stakes are surrounding the beliefs.

A lot of the research surrounding cognitive dissonance is in how it drives people to find ways to justify or rationalize behaviors. What’s not discussed much (except, interestingly, in Public Relations and Advertising circles) is how cognitive dissonance can be exploited to nudge people toward certain behaviors, like buying a particular product or engaging in pro-social behaviors (such as recycling). What I find interesting is the potential for leveraging cognitive dissonance in education to increase engagement and retention.

Consider this example from 4th/5th grade science:

What Floats? Working in groups, give kids a container of water deep enough to float several pieces of fruit. Give each group a set of fruits: a grape, an orange, a strawberry, an apple, a kiwi, etc. Make sure the fruits are different sizes. Provide a scale that measures weight in grams. Have each group weigh pieces of fruit and record the weights. Then have the group predict which pieces will float and which will sink when placed in the water. After that, place each piece in the water and note whether it sinks or floats. Discuss in groups what surprised them and possible reasons why they got these results. Using a knife, have kids cut the fruits open and note their observations on the internal structure. Ask how this helps explain their results.

Kids will predict that the heavier and larger pieces will sink — apple, orange, etc. — and the smaller will float. What will actually happen is that some of the smaller pieces (grapes) will sink because they are denser than the larger pieces. Because the kids believed one thing would happen, the fact that something unexpected occurred is instantly engaging — the teacher has just leveraged a little low-stakes cognitive dissonance to increase their cognitive engagement and retention around the concept of density. Note that the experiment walks kids through their own predictions surrounding size and weight before the sink/float test — this activates their own beliefs and understandings (schema) and makes the dissonance a little sharper when it doesn’t fit what they think they know. I’m calling this low-stakes because no one is going to die on the hill of float predictions in elementary science.

Here’s an example of raising the stakes: In Algebra I, the teacher places students in groups. Each group is responsible for solving a complex problem requiring the skills of all the members. The group receives a grade based on the performance of a random member chosen to present and justify their solution. The cognitive dissonance here is multi-dimensional and falls into the same category as culture shock — the differentness of the activity compared to what kids are used to.

- Not being told how to solve the problem is going to be productive of serious cognitive dissonance in kids used to the teacher showing them how to do something and then giving them a slate of practice problems so they can memorize the method. Even the fact that there might be multiple ways to get the right answer may be frustrating for those looking for a single method provided by the teacher.

- Most students are used to being assessed on their individual performance; some may prefer not to have their grade tied to someone else’s abilities. This is a big shift in the purpose of the activity — not to understand it yourself, but to ensure that everyone understands it. Even the necessity of relying on another’s understanding to solve the problem may be disorienting, since math is frequently an individual activity.

- Justifying the solution is something that some students may or may not be familiar with. For students used to replicating a process (as demonstrated by the teacher) and getting the right answer, the process of figuring out your own solution (recognizing that there may be multiple ways to solve the problem) and justifying how you got your answer may be frustrating and disorienting.

Because the stakes are higher here (individual performance, graded work, potential perception that the teacher isn’t “teaching,” etc.) the cognitive dissonance is greater and potentially more upsetting to the student. The teacher will have to design classroom experiences very carefully and provide extensive support to groups. I would say that the stakes are high enough here that people outside the classroom could end up involved (parents, principal) if the teacher isn’t careful with the design of the activity. But, there’s tremendous potential here for accessing higher order thinking and for increasing both understanding and retention of concepts because of the cognitive dissonance produced by the novel group work and expectations. (Read more about this kind of math approach here). And, once kids are used to the new paradigm, the cognitive dissonance will recede.

I can’t swear that leveraging cognitive dissonance will always lead to the employment of higher-order thinking skills, but I suspect that it may have that effect more often than not as long as the activity is carefully designed and managed so that the student doesn’t check out due to the discomfort engendered by the activity. The cognitive dissonance should be a little uncomfortable, not excruciatingly painful.

image via skeptical-science.com

There’s one other area where cognitive dissonance can be used to great effect and that’s in social justice education. Often this is employed in disrupting long-held ideas and beliefs about the United States, such as how Europeans founded this country. Cognitive dissonance arises when we point out that this country was already populated with several million indigenous people, so “founding” might be better replaced with “conquered.” Beliefs in this area range from low-stakes (George Washington never cut down a cherry tree) to high-stakes (the framers of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution weren’t actually Christian at all but more accurately Deists) depending on the audience. To go deeply into this isn’t possible in this space, but you can read about it in Paul Gorski’s excellent article. Two key aspects from this piece: 1) Kids need vocabulary to recognize and name their own cognitive dissonance so they can understand their responses to new information that challenges a long-held belief or attitude. Being able to define and name their responses goes a long way toward integrating new content. 2) Discussing cognitive dissonance can’t be allowed to hijack the activity. The dissonance can be noted and named as an affirmation of what a student is feeling, but the focus of the classroom activity remains the learning. If more processing is necessary, students can journal about how something made them feel or how their beliefs were challenged by a particular lesson.

One last note: Teachers may also experience cognitive dissonance, with all the same discomfort and potential responses. One way this can occur is when teachers use programs the district tells them to use, following content the district dictates, but don’t see improvement in their students. If the district then blames teachers for the lack of achievement and doubles down on enforcing content and resources, teachers can end up living in a dissonant state in which effort and results are disconnected. A very common response to this is to end up blaming the students for the poor achievement (rationalizing the behavior). Cognitive dissonance can also occur when teachers undergo diversity training and learn new information about implicit biases, microaggressions, inequitable practices, and so on. Our country has experienced some of this as we seek to reexamine our understanding of race relations in the U.S. It may even be fair to say that some of the pushback from state legislatures surrounding the teaching of Critical Race Theory stems from cognitive dissonance; remember, one of the responses to cognitive dissonance is rejecting the new information. Not coincidentally, the often-cited reason for the pushback is that CRT makes some people feel guilt or shame, a common product of cognitive dissonance. Some state legislatures have even sought out resources designed to bolster existing Euro-centric history content (confirmation bias — another response).

Cognitive dissonance can play an important role in assimilating new information and interpreting old information. Sometimes we need to break things down a bit to build them up better and stronger than before. If we recognize where dissonance is likely to occur and help kids name it and recognize their own responses to it, and if we help them take some ownership in the processes and outcomes of new learning, cognitive dissonance can help them integrate new concepts more easily and at more depth.

Cognitive Dissonance = Mind. Blown. (Almost) literally.