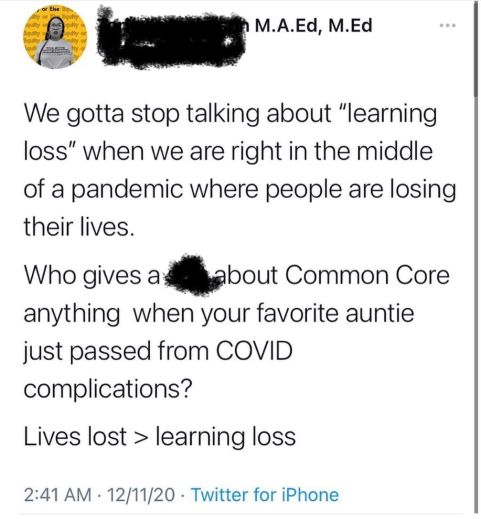

Recently I saw this tweet from an educator. It’s arresting for two reasons: her distress is evident and searing, and her assertion is a little shocking. Forget entirely about learning?

Recently I saw this tweet from an educator. It’s arresting for two reasons: her distress is evident and searing, and her assertion is a little shocking. Forget entirely about learning?

So, then I started really thinking about this and why I found it shocking. And I realized it’s because in my community, while I know a couple people who have died or lost loved ones to Covid, no one I am close to has died. In fact, death rates in my immediate community are relatively low. Also low is the percentage of people who have lost jobs because of Covid layoffs. I have been relatively insulated from the worst of the effects of the pandemic because of my middle class neighborhood, because of my 2-income, salaried household, because of my ability to work from home which includes not just the type of job I have but also the ability to pay for infrastructure (fast wifi) that enables me to do that while my husband and all 3 of my children are also online for work and school. I have a tremendous buffer between me and the pandemic that has allowed me to continue to nag my kids without guilt to do their homework, study for tests, retake or redo things they messed up, and so on. But my experience is not the same as others’ living just 5 miles away.

In my wider community, the rate of unemployment is high as people who work as waitstaff, bartenders, dishwashers, hair stylists, and retail staff have lost their jobs or had their hours slashed. The rate of eviction has risen, and even though my state has placed a moratorium on evictions until January 1, this is only a temporary stay: all that back rent is due January 1 and people still won’t be able to pay it because they still aren’t working and may not be working until next summer or later. Without intervention, this is going to lead to a massive surge in homelessness. The original stimulus checks didn’t really make a dent in this because they covered only a month or two worth of rent at best. Black and brown people in my state are getting sick at higher rates than white people because many can’t work from home or they were classified as essential personnel because they work in grocery stores or food processing plants. Demands on local food banks are outpacing supply and are continuing to grow. Pre-pandemic, 12 million kids were food insecure; that’s 1 in 5 kids overall, rising to 1 in 3 among African-American and Latino children. Estimates now are that 17 million kids are food insecure. Many people don’t have employer-provided health insurance (hourly workers usually don’t and some places deliberately keep hours just under 40/week to avoid having to provide benefits) so seeing a doctor or going into the hospital is entirely out-of-pocket and crushing financially. Increasingly, this is true even for those with employer-provided health care, especially if they have high-deductible insurance. The urban poor often don’t have clinics or even pharmacies in close proximity, and that lack of access may lead to difficulties in getting people vaccinated. The problem of access is even more complicated in rural areas.

All this to say, that we need to really think about how we respond to students and families during the pandemic. If a child isn’t learning, we can’t assume any kind of willful intent, nor can we assume some sort of parenting failure. We need to make a point of understanding conditions in the community and in individual families and for that I suggest the following for everyone from district administrators to principals, teachers, and support staff:

- Know how Covid is impacting the community in which your students live. What is the current unemployment rate? What’s the housing situation? Is there an eviction moratorium? What is the current positivity rate for Covid-19? What do area food banks say about demand? If your district is providing meals or meal pick ups, what is the response? Survey parents to see who is experiencing one or or more of these issues. Seek ways to connect people with services or help — housing assistance, food banks or food distribution sites, organizations helping to offset health care expenses, translators to help people apply for assistance.

- If you live or teach in an economically disadvantaged district or school, assume trauma has occurred. Assuming trauma will better shape your responses to students who have experienced it and it won’t harm those who haven’t. Communicate with school staff so everyone is aware when a severe trauma has occurred — a family death, loss of job, loss of housing, etc. Make every effort to connect kids who are struggling with whatever resources are available — school nurses, psychologists, learning specialists, counselors. If your school doesn’t have these people or services available, now is the time to demand the district provide them.

- Lead with Social-Emotional Learning, then Academic. The tweet above was correct in one important sense: a mind experiencing trauma can’t learn. Many regress academically in the face of trauma, so pressing a traumatized child to achieve academically is fairly pointless, but it’s hard to know when the child has passed from trauma to sufficient healing to learn again so abandoning learning entirely is probably not a great idea either. The classroom can provide a safe, predictable routine in the midst of chaos. This is where teachers need to focus more on the relationship with the student than on the student’s learning; really knowing your students helps you assess their needs. Work to make school a safe, secure place. View behavior — especially newly disruptive behavior — through the lens of trauma and seek to give kids a place where they can express feelings but not hurt themselves or others or disrupt the classroom. Give all kids the vocabulary to describe feelings and healthy ways to vent.

- Expect the effects of the pandemic to last. Plenty of evidence from Katrina and other disasters has demonstrated that the effects of the pandemic are going to be around far beyond its logistical end. Children from heavily-affected communities will need ample empathy and support for the next few — maybe even several — years. And remember that the ones with the least impact and the most resources will bounce back fastest; there will be extensive work to be done in marginalized communities even when the rest of the world puts a period on the Covid-19 experience.

- But Expect Healing to Occur. Focusing on Culturally Relevant Instruction (which encompasses SEL) to get kids back to to speed with their peers will be a critical tool in recovery. And that’s the end goal of CRI: success for all, achievement for all.

Know your learning community, do what you can to care for their physical and emotional needs, remember that your experiences are not everyone else’s, lead with compassion, extend grace, prepare for the long haul, stay the course, have faith.