Student work artifact collected from an audit in 2019

One area in which districts must be vigilant is in the vetting of resources. Resources must be vetted for a variety of reasons, including alignment to the district’s curriculum and to external assessments in use, but resources must also be vetted for bias – language or imagery which employs racist terms, perpetuates stereotypes, marginalizes certain groups, or seeks to minimize or discount their experiences.

In the process of analyzing student work artifacts, auditors encounter many resources from large publishing houses and purchased resource packs all the way down to activities marketed on Teachers-Pay-Teachers or similar websites. Because the pool of available resources is so vast, it is relatively easy for biased language and imagery to slip by unnoticed and unchallenged. Some of these examples of biased or minimizing language are well documented:

- In 2015, the mother of a Houston, Texas student drew attention to a McGraw-Hill geography textbook which explained that “workers from Africa” were “brought” to the U.S. to work on plantations. The book included a map which listed Africans in the map legend as an “immigrant group” along with the Dutch, Germans, Irish and others.¹

- American Pageant, a textbook for AP U.S. History which was still in use in 2020, listed Africans as an immigrant group among other immigrants such as the Scots-Irish, implying that they freely chose to come to the US. The 16th edition of this book, which was in use until 2019, also contained passages such as this one: “In the deeper South, many free blacks were mulattoes, usually the emancipated children of a white planter and his black mistress.” (p. 346) Mulatto is a racist slur for a biracial person. The casual reference to the white planter’s “black mistress” implies a consensual relationship rather than one in which the enslaved woman had neither choice nor agency. And while some free Black people may have been freed biracial children of white planters, many more of these children remained enslaved.²

- Texas History, a middle school social studies textbook published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, contains a caption about slaves, who were brought to Texas to “help work the fields and do chores.” As Ibram Kendi noted, chores are things you do that you don’t want to do; slavery is being forced to do something because to not do it threatens your physical wellbeing or even your life.²

- Mexican American Heritage, the only textbook submitted to the State Board of Examiners in Texas for a proposed Mexican-American Studies Course in 2016 contained passages such as this: “[Industrialists] were used to their workers putting in a full day’s work, quietly and obediently, and respecting rules, authority, and property. In contrast, Mexican laborers were not reared to put in a full day’s work so vigorously. …There was a cultural attitude of ‘mañana,’ or ‘tomorrow,’ when it came to high-gear production. It was also traditional to skip work on Mondays, and drinking on the job could be a problem.”

CMSi has also encountered bias in resources, including:

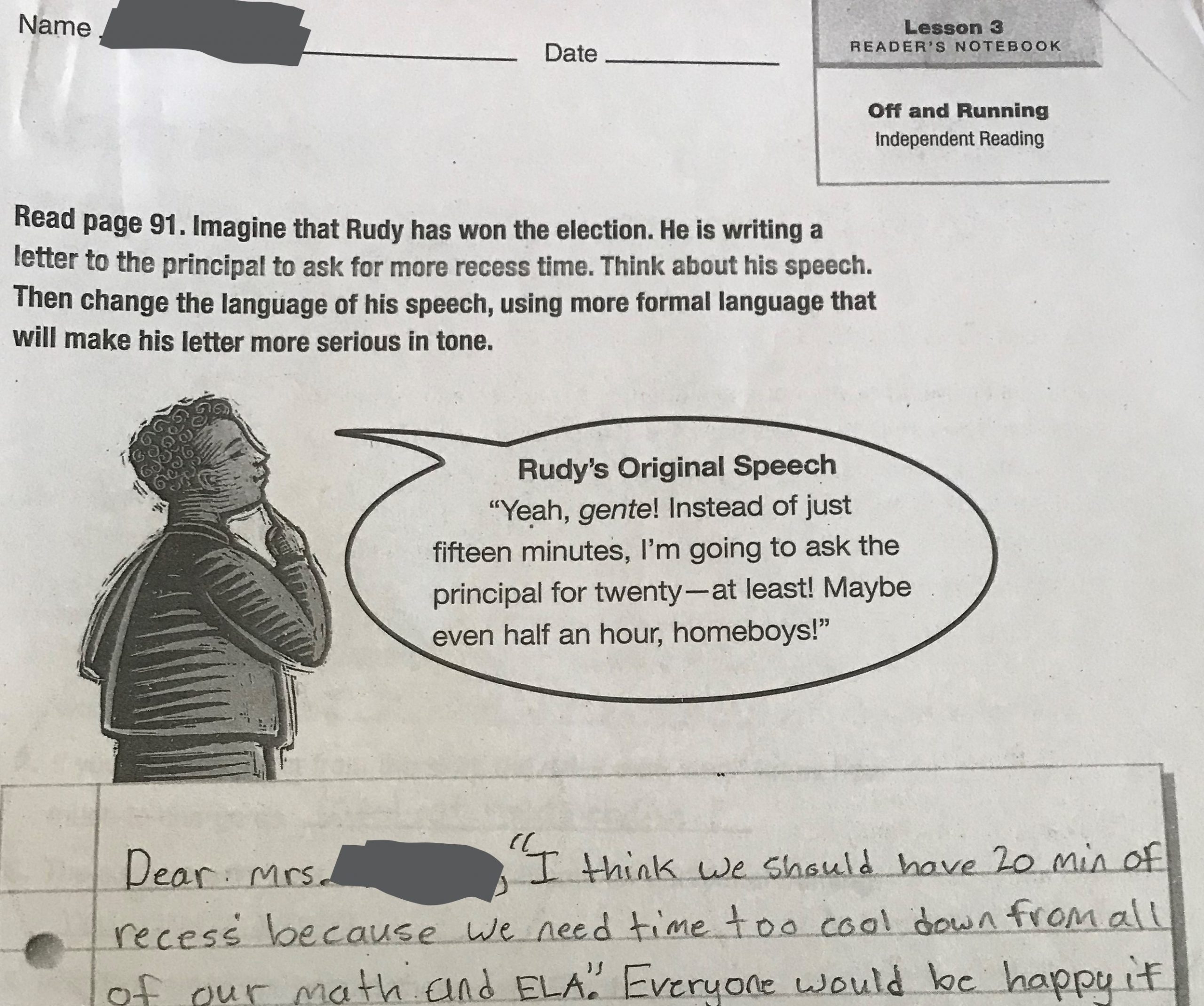

- A Houghton Mifflin Harcourt reading workbook (see above), collected from an audit in October 2019 in which a Hispanic student named Rudy is writing a letter asking the principal for more recess time. Rudy says “Yeah, Gente! Instead of just 15 minutes, I’m going to ask the principal for twenty – at least! Maybe even half an hour, homeboys!”

- A 2020 worksheet from a teacher-created resources site introduced students to the Indian Removal Act of 1830. This is commonly known as the Trail of Tears and involved the Cherokee tribe’s forced and brutal removal from the Eastern U.S. to Oklahoma, an event which cost many lives. The worksheet includes boxes for students to record major events. Each box has two small, cartoonish Native American figures behind it, leaning forward. The figures are wearing stereotypical Plains Indian dress which is nothing like the clothing worn by the Cherokee. All are smiling. A detailed line drawing of a Native American man’s head and neck appears next to the title “Indian Removal.” This figure is also smiling.

Still other textbooks include or omit information based on what they feel is most palatable to the purchaser:

- A recent investigation by the New York Times revealed that social studies textbooks from the same publisher but customized for the Texas and California school markets, were markedly different in how they presented a number of topics, including the Civil War and its aftermath. Southern whites resisted Reconstruction, according to a McGraw-Hill textbook, because they ‘did not want African-Americans to have more rights.’ But the Texas edition offers an additional reason: “Reforms cost money, and that meant higher taxes.” This rather oversimplifies the pushback against Reconstruction to a dispute over taxes; especially when many primary source documents explicitly list the opposition to more rights for former slaves and the restoration of the South to its former glory as motivating factors. Whole paragraphs on redlining and restrictive deeds — policies whose negative effects still reverberate in communities today — appear only in the California editions of textbooks, partly as a result of different state standards.³

Or they fail to address groups in anything other than a historical context, as though they ceased to exist (or at least have any relevance) after a certain point in history. This is particularly true of how Native Americans are presented in history texts.

All of these resources are problematic and detrimental for both students of color and white students alike. For students of color, such resources reinforce — and perhaps help internalize — negative stereotypes, and devalue their and their ancestors’ contributions to the growth and development of American Society and the American economy. For white students, particularly those who have few or no students of color in their schools, such resources subtly and not so subtly reinforce ideas about White superiority or reaffirm a White Redemption Narrative — wherein people of color would not survive or thrive without White intervention and correction.

Vetting for bias is critical; equally critical is the need for districts to provide a robust selection of quality, unbiased resources – resources that affirm the contributions of multiple groups and honestly discuss the failings of some groups in their interactions with others. Many of the examples above were discovered by parents or students of color who recognized the ways in which the textbooks were devaluing their contributions or attempting to reframe their negative experiences as something less pejorative. Students of color can and do recognize when they’re being gaslighted. Making sure that teachers and parents can (and do) vet resources with an equity lens before adoption is an important level of transparency for districts. Once vetted, teachers need enough of these bias-free resources to have ample choices suitable for diverse learners and multiple ability levels. Maintaining such a pool of good resources decreases the likelihood of bad ones creeping into the mix.

_______________________________________

¹ Immigrant Workers or Slaves? Textbook Maker Backtracks After Mother’s Online Complaint https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/10/05/immigrant-workers-or-slaves-textbook-maker-backtracks-after-mothers-online-complaint/

² CBS News Special Report https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-american-pageant-map-in-widely-used-us-history-textbook-refers-to-enslaved-africans-as-immigrants-cbs-news/

³ Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/01/12/us/texas-vs-california-history-textbooks.html?algo=top_conversion&fellback=false&imp_id=281113599&imp_id=992135319&action=click&module=trending&pgtype=Article®ion=Footer