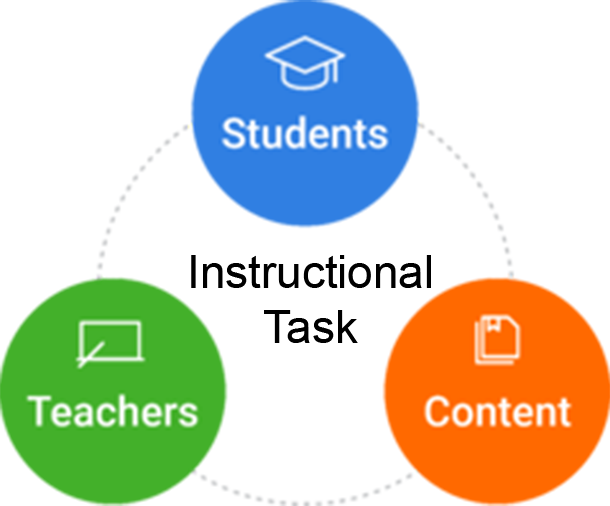

The Instructional Core, as defined by Richard Elmore, is composed of a teacher and student in the presence of content. The relationship between these three elements, and not the the qualities of any one element, determines the nature of instructional practice. At the heart of this trinity is the Instructional Task: what students are being asked to do in the classroom. Elmore is quick to qualify this by saying that the Instructional Task is what students are actually doing, not what teachers think they’re being asked to do or what the curriculum says they’re doing. If a student in Advanced English class is asked to memorize a list of literary terms, that Instructional Task is memorization: the lowest level of cognition on Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy. It doesn’t matter that the course is “Advanced;” the thinking skills required aren’t.

Elmore says there are only three ways to improve student learning at scale — in other words, more than just one or two classrooms:

- Increase the teacher’s instructional knowledge and skill (capacity)

- Increase the level of complexity of the content students must learn

- Change the role of the student in the instructional process

Everything else in the school or district is important only insofar as it affects the core. A great example of this is the presence of technology. Technology has the potential to affect the core, and it can certainly seem cutting edge, but if the tech only substitutes for static resources it can’t really affect the core. Students doing worksheets on an iPad are still doing worksheets. Another example would be environment: the ability of students to engage in the instructional process can be adversely affected by environmental issues such as vermin, heating/cooling problems, violence, and hunger. The bottom line is, a district can have all the bells and whistles it wants (or conversely, be as spartan as a monastery), but it’s irrelevant unless it affects the Core.

Here are a few other things that may, or may not, affect the Core:

Professional Development – If it affects what teachers do (not what they think or what the trainer believes the training provides) in the classroom, then it affects the Core.

State Standards — These affect the level of the content but not necessarily the other two parts of the Core. If the teacher doesn’t know how to teach the content or the students don’t find it meaningful and engaging, it will not increase learning.

Grouping — If it enables the teacher to teach more effectively and the student to have access to higher level content and it provides a greater degree of engagement. Otherwise, it’s just an ancillary process that doesn’t affect the Core.

Instructional Leadership/Monitoring/Mentoring — If it helps teachers develop greater instructional skill and capacity and/or impacts the level of work in classrooms and/or increases student engagement. The potential is there, but it has to affect what teachers do. Simple evaluation of teacher performance is unlikely to provide any of these things.

You may have noticed here that the interconnection of the three elements of the Core helps us explain why “improvements” often go awry even when they affect the Core in some way: one of the fundamental principles of the Instructional Core is that if you change one element, you have to change the other two. You may have wonderful content but if teachers don’t know how to teach it, it won’t (in and of itself) improve learning. You may have engaged students but if the content is low level and confusing or perceived to be of little use to the students, learning will not improve (and engagement will erode). You may have teachers with a great deal of skill but if the role of the student in the instructional process is not fundamentally altered you’ll end up with teachers doing most of the heavy lifting while students passively absorb content.

The takeaway here is that the Instructional Core, and only the Instructional Core, has to be at the center of any improvement efforts a district undertakes. Every system, protocol, and process, every dollar spent or withheld, every decision has to be arrived at through an understanding of how it impacts the Core. To do otherwise would be to risk spending precious resources with no guarantee of positive return. The question of how the Instructional Core is affected, along with its sister question, “what are students actually being asked to do to demonstrate mastery?” form the lens we use at CMSi to evaluate district systems and processes and the work of classrooms and the basis for nearly every training we offer.

If your district is interested in understanding how the Instructional Core is functioning for you, Contact Us! We would love to help you with a Curriculum Management Audit™ or Student Artifact Analysis or Curriculum Writing Training to better focus your efforts to improve student learning.