Image via Anaheim Elementary School

“When we treat a person as only as we think they are, we make them worse. But if we treat a person as if they were already what they could be, we take them as far as they can go.” — Goethe

Possibly my favorite piece of research ever is from 1985. It’s an oldie, but oh so good. It involved the question of how students were identified for Gifted and Talented education. Traditional means such as IQ tests have long come under fire for being racially and economically biased. What would happen, researchers wondered, if they took a bunch of kids who had not been identified for GT and evaluated them for potential giftedness?

They used a battery of non-traditional identifiers, including peer surveys (Who tells the best stories? Who always knows the answers? Who is good at building things?), teacher recommendations, and some cognitive/developmental identifiers and came up with a pool of potentially gifted students. And then? They spent the next year treating them like they were gifted.

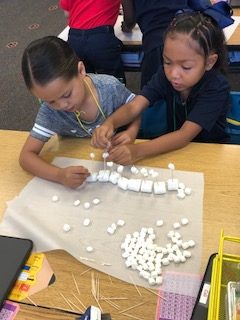

They gave them opportunities to go deep on subjects that interested them and opportunities to explore tangents that struck their fancy. They gave them lots of opportunities to do hands-on activities that were cognitively engaging. They also provided them with additional supports — especially in verbal and writing skills which some needed extra help with to get up to speed with their grade level peers.

At the end of the school year, 40% of the potentially gifted students went on to be identified as gifted under the system of traditional identifiers. That’s a phenomenal percentage.

What is striking about this research is the idea that people — students — so often live up to exactly the expectations their teachers have for them, good or bad; they may fail because the teachers treat them as though they have already fallen short or they may succeed because someone treated them like they were gifted. Equally striking is that the researchers didn’t just drop the kids into the deep end of the learning pool and hope they’d figure out how to swim. They provided plenty of support for the skills that were lacking or lagging. Giftedness, then, is something to be enabled and nurtured, not just an innate ability that some have and some don’t. In our experience, all children benefit from high expectations and the support necessary to achieve them. It looks as though there are many more “gifted” children out there than are actually identified as such.

Helping every kid reach his or her potential has tremendous implications for society as a whole. Remember Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett? One teacher spotted her potential and told her parents to seek out the best, highest, most advanced classes they could for her. Now she’s a leading figure in coronavirus research. Dr. Katherine Johnson had a similar story: pushed to excel by teachers, she began high school at age 10 and ended up as a mathematician for the NASA Space Program. When students are pushed to excel and given the support to do so, it benefits everyone. May we all treat our students like they’re going to solve the cold-fusion problem or find the cure for cancer. If we treat them like they will, they just might.

If you’d like to read this old, but wonderful, piece of research for yourself, the citation is as follows:

Johnson, S., Starness, W., Gregory, D., & Black, A. (1985). Program of assessment, diagnosis, and

instruction (PADI): Identifying and nurturing potentially gifted and talented minority students. Journal of Negro Education, 54(3), 416-430.