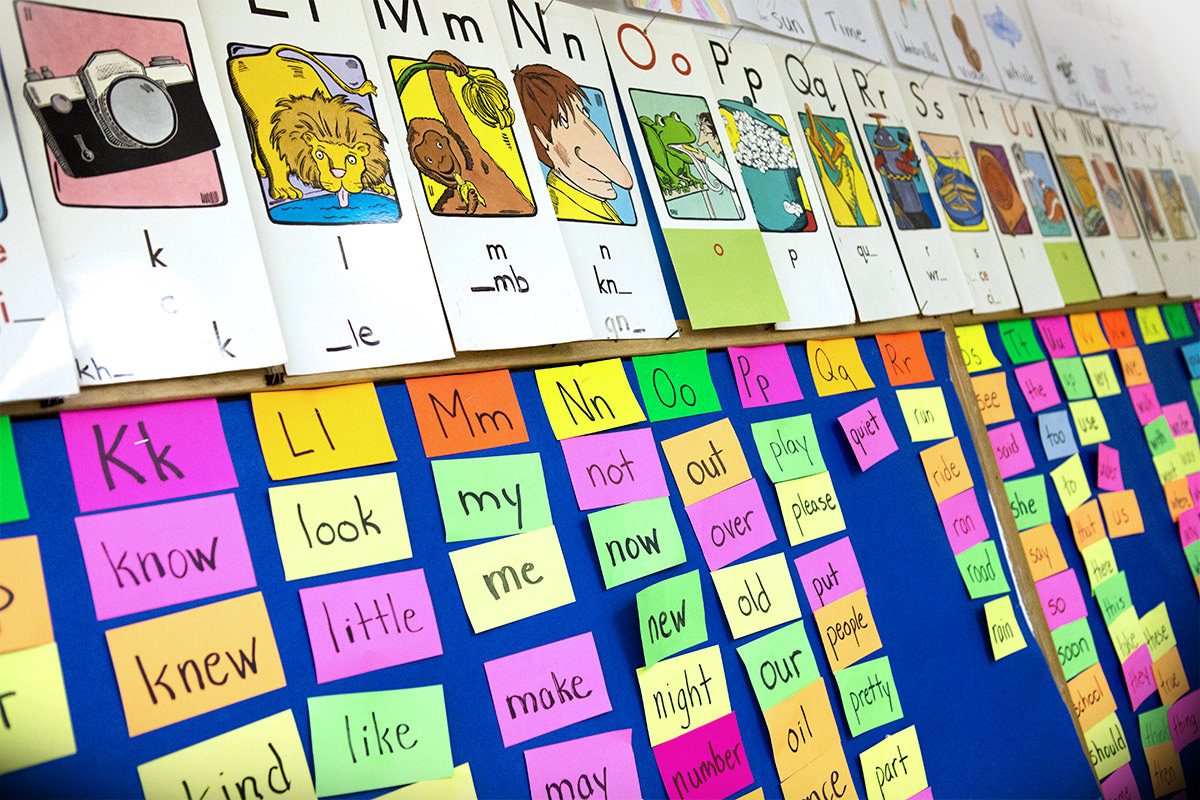

image via aspire.org

In the last post, I talked about several things that are in danger of being eliminated in the push to get rid of balanced literacy programs. One of those things — Miscue Analysis — has already been more or less banned in Texas. I have been told, but can’t confirm independently, that this was the result of a lot of parents with students who have reading difficulties pushing to eliminate all “cueing” from reading programs because they believed it was a harmful strategy for struggling readers, particularly dyslexic students.

It appears — and again, I can’t verify — that some key terms have been conflated. Dispensing with miscue analysis is problematic because it’s a very important diagnostic tool for teachers.

My unconfirmed hunch is that parents were objecting mainly to 3-cueing. This is a strategy where a child encounters an unfamiliar word — let’s say porcupine — makes a guess as to what the word might be, and asks three questions to try to determine whether their guess is correct — the 3 cues. Those questions are: Does it look right? Does it sound right? Does it make sense? So if the child guesses pancake instead of porcupine and then asks the 3 cues, hopefully they will stop after cue #1 because p-a-n-c-a-k-e doesn’t look like p-o-r-c-u-p-i-n-e and the sounds their respective letters make do not align. If, however, they don’t stop there, then they’re supposed to listen to how it sounds in the context of the sentence. If that doesn’t confirm their choice, the next cue is to ask whether it makes sense in the sentence. The pancake waddled through the forest shaking its spines. Hmmm…probably not pancake. So the child needs to find a different word to try. This is a strategy deployed by the student as they read.

Miscue analysis is a critical diagnostic tool that helps teacher determine why a child is reading text incorrectly. The problem can lie in one of several areas — it might be a phonics issue (grapho-phonemic), but it might also be that they don’t have extensive exposure to the language (as for ELLs) and are reading incorrect words because they don’t know the correct word. The teacher really needs to know why a kid is making mistakes so they can tailor the instruction to suit the problem. Miscue analysis is deployed by the teacher as s/he seeks to address reading problems.

3-cueing works for kids who know a lot of words and for those who come to school already reading. If a child has been exposed to a lot of language, and particularly to a lot of written language in the form of books read to them, they have a good sense of how written language works — of what’s possible or likely. Their chances of guessing a word that’s in the ballpark are greater than kids whose vocabularies are smaller and/or who haven’t been exposed to a lot of English, like ELLs. Why this is true connects neatly with with how the human brain processes, analyzes, and stores language.

image via children’s literacy initiative

In Mark Seidenberg’s excellent book Language at the Speed of Sight, he talks at length about how kids learn to read and some of the neural processes that support that skill acquisition. He makes the point that a child’s brain is continually engaged in amassing a kind of database of language. That database allows the child to “check” new words and phrases against what they already know about how language works. The more exposure to language, and the more exposure to written language (which differs in significant ways from spoken language), the more information in the database that the child can draw on as needed. If you have ever done the Wordle, you have a window into understanding how this process works. When you are confronted with a few letters and have to guess what word they spell, you begin trying and rejecting possibilities. As an adult, you have by now a fairly massive database at your disposal that tells you what letter combinations are possible in English and which combinations are not. You can come up with several possibilities that fit a particular letter configuration and the letters you haven’t used yet. If you have __ __ a t e you know that grate, slate, crate, skate are all possibilities but gnate, brate, clate are not. Over decades of reading, listening to, and speaking English, your brain has amassed billions of bits of information that you can deploy in algorithms that let you search for and eliminate possibilities when you encounter something not explicit, unfamiliar, or straight up obscured.

image via youtube.com

It’s not hard to see how a child who hasn’t had a lot of exposure to language, especially written language, won’t have the same database as a child with extensive exposure. They don’t have millions of words or linguistic interactions in English to which they can compare new words or unfamiliar syntax. If they are making mistakes , it’s critical that the teacher understand why they are making them. More sound-letter awareness doesn’t really help a kid whose problem is lack of vocabulary. And in science of reading programs there is can be a blanket assumption that when kids make mistakes it’s because of some grapho-phonemic issue that can be ameliorated by more phonics work, even though that may not be the case at all.

Here’s an illustration of what I mean: I’ve been privileged this fall to work with a group of 4th grade ELLs. Most of them can read in their native language so they are picking up decoding English words relatively easily. But decoding isn’t really their problem. Their problem is that they don’t know what things mean. They can sound out c-o-t, but don’t know what a cot is.* If we look only at simple decoding, they look pretty good, but their real need (vocabulary and meaning-making) will not be addressed and will eventually be obscured by their growing fluency. This is why miscue analysis is so important.

So here’s my non-reading teacher conclusion: BOTH balanced literacy and science of reading programs are capable of failing kids if the teacher doesn’t understand why the program isn’t working for them. The teacher needs a range of tools to figure out where the problems is and fill in the gaps in the program** by differentiating instruction for that child and tailoring strategies that help him or her improve decoding, or make meaning, or build vocabulary. Diagnostic miscue analysis should remain in teachers’ tool boxes to ensure we don’t lose this critical window into the barriers students face when learning to read.

*This is a common issue with ELLs: they get really good at decoding and can do it fluently, but semantically it’s gibberish. They have no clue what a lot — or even any — of it means. Decoding, however, is often equated with comprehension — surely such fluent readers must understand what they are reading, otherwise how could they be so fluent?

**ALL programs have gaps. There is no program that meets everyone’s needs perfectly. This is why teachers need to deeply understand how to differentiate and scaffold for a variety of abilities and needs and learning styles. There is NO SUBSTITUTE for differentiation.