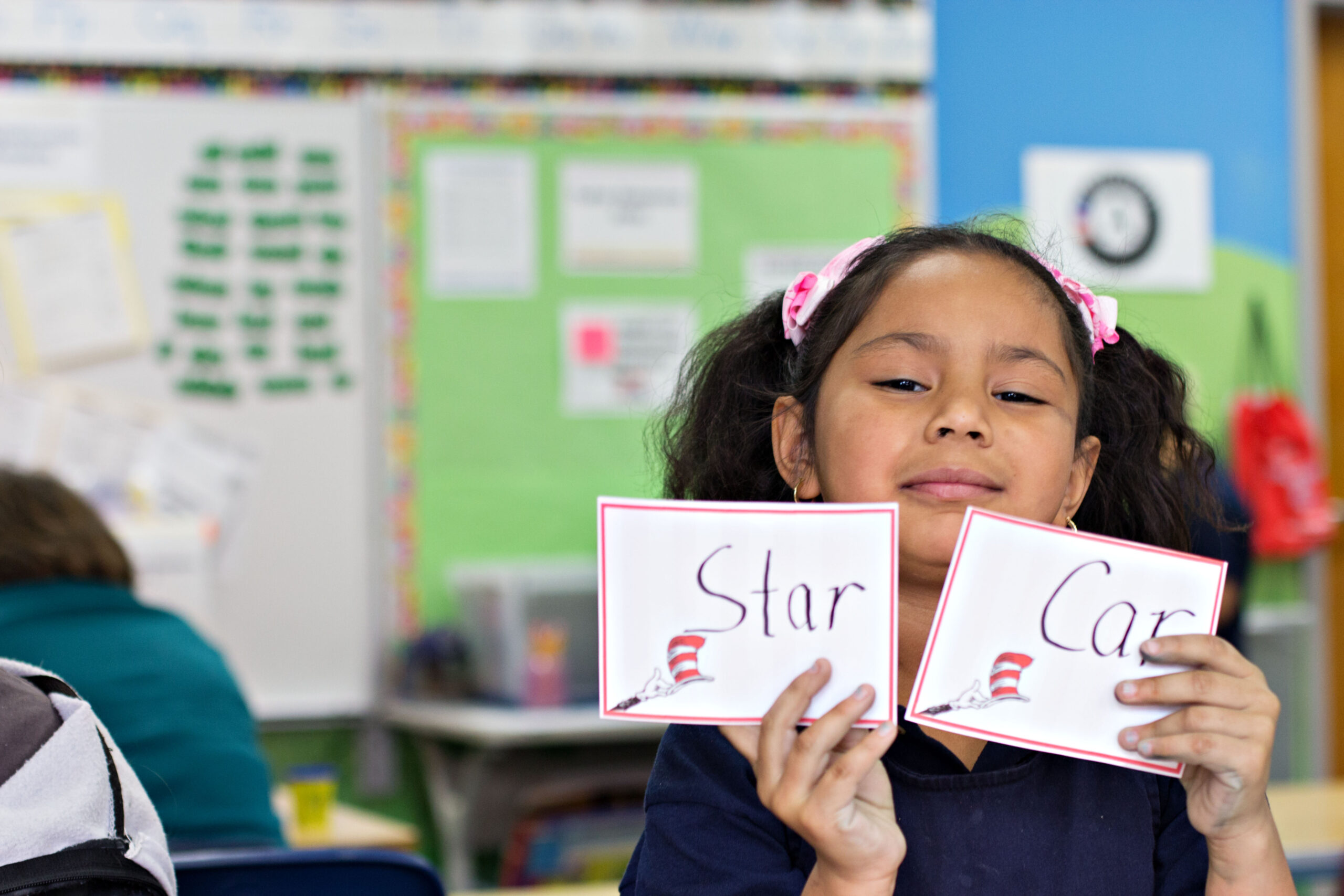

image via childrenrising.org

There’s been a movement over the last several years to replace “balanced literacy” reading programs* with the “science of reading.” As of now, the science of reading is winning. More than 30 state legislatures now require reading programs to utilize the science of reading and more are poised to require it. Proponents for both types of programs can be passionate in their defense and the arguments between the two philosophies has played out in articles, podcasts, and scholarly research. Without taking a side (more on why in a minute), I’m going to offer a quick description of the major arguments for and against each.

One of the biggest knocks against balanced literacy is that two of the major purveyors of classroom resources may have been actively discouraging teachers from combining the program with basic phonics instruction. Instead, the programs were based on the idea that “good” readers used pictures and context to approach unfamiliar words and make an educated guess as to what it might be. This was codified into the “3-Cueing” system. The 3 cues students were to use were: Does it look right? Does it sound right? Does it make sense? There is significant scholarly debate and even outright refutation that this is what good readers actually do. Research dating back 40 years demonstrated that less good readers use context and pictures to figure out words because they lack the sound-letter correspondence skills to sound them out. If you talk to people about these programs, they will tell you that of course phonics were taught along with the 3-Cueing; but some of the programs themselves explicitly instructed teachers not to teach phonics because children would figure it out on their own without them. Only when a child demonstrably did not learn to read were they placed in Reading Recovery, a remedial (their word, not mine) program that taught basic phonics principles. When a child was placed in RR could vary widely depending on multiple factors. He or she might lose one or even two years of reading instruction before they were identified for this intervention. The aspect of balanced literacy that everyone agreed was excellent was the literature itself: meaningful, beautifully illustrated, authentic texts by actual authors that were very appealing to children and therefore motivated them to read. Since teachers are themselves good readers and want to instill that love of reading in their students, this literature was inspiring. Now, not all balanced literacy material was at this standard — that varied by the company providing it — but in general it was pretty good stuff.

The science of reading, which we used to call ‘phonics” until it got a publicist, has a lot of, well —science — behind it. Research dating back multiple decades supports the direct instruction of letter-sound correspondence and the systematic instruction of patterns in spelling (and, of course, all those spelling renegades that make English so frustrating to learn to read). This has the advantage of being able to keep track of what’s been taught, what the child has mastered, where they need more work, etc. It is also the source of a lot of common vocabulary around reading — digraphs, consonant blends, CVC words, word families, etc. The big knock against the science of reading? It’s easy to lose sight of the forest for the trees, getting so bogged down in the mechanics of reading that the meaning of what’s being read is incidental or even unimportant. Being able to decode the words is key and the actual story is secondary. And the literature associated with science of reading programs is often pretty grim: stories written purely to incorporate words from a particular family or that use a particular digraph or lots of examples of silent e or whatever. These generally don’t engage kids to any great degree — they’re not relevant and they’re lacking in finesse across the board, often flimsy and poorly illustrated and composed by company writers rather than actual children’s authors.** They do not appear capable of inspiring kids with a love of reading.

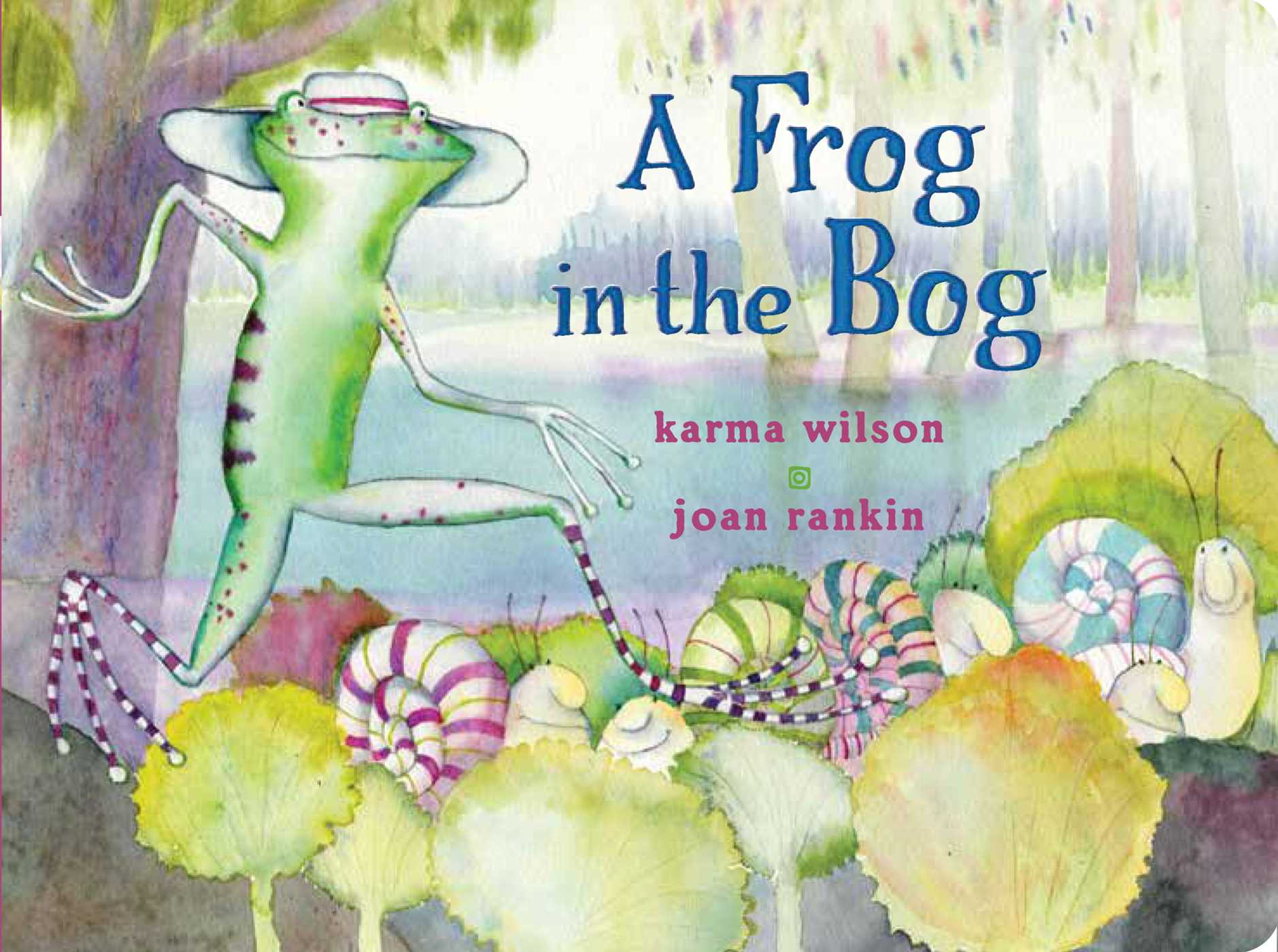

image via readingparnters.org

Here’s why I’m not taking sides: both approaches have valuable features. Reading as a skill doesn’t just occur. It has to be taught. Kids need direct instruction to help them crack what is essentially a giant coding system for spoken language. Like any other kind of instruction, some are going to need more of it for longer and some are going to take off immediately.*** But kids also need rich, authentic, meaningful literature that engages them and motivates them to read more. They need more than just the nuts and bolt of reading — they need the poetry and the music of it as well. To not give them this is like looking at the keys and strings and pedals of a piano and ignoring its central purpose: to communicate emotion through music. Endless lessons about the structure and functions of the piano will get boring fast; music is endlessly entertaining and that entertainment creates greater motivation to continue.

This is a fundamental problem with education: the pendulum swings wide and educational practices tend to fall at the farthest ends of the arc. Reading instruction without phonics is at one end, phonics without meaningful literature is at the other. Best practice lies between the those extremes. There’s already evidence that some places are throwing the baby out with the bathwater as they ditch balanced literacy in favor of phonics. As part of their push to eliminate the 3-cueing practices that are part of some balanced literacy programs, Texas has inadvertently banned miscue analysis, which is not at all the same thing. Miscue analysis is very important for reasons I’m going to discuss in the next post. Guided reading may also end up a casualty of the balanced literacy purge, even though it is a helpful way for teachers to model thinking and help students make meaning from what they are reading. This is accomplished in small groups that allow the teacher to differentiate instruction or texts depending on the progress the students have made. Making meaning is critical to getting kids to buy into reading — it’s the difference between a rich, interesting story and reading meaningless lists of words. Here are two examples:

Phonics Reader:

“The hog can jog. The hog jogs in the bog. The hog jogs in the fog.”

Authentic Literature:

There’s a frog on the log in the middle of the bog./A small green frog/on a half-sunk log/ in the middle of the bog./He flicks ONE tick/ as it creeps up a stick./ONE tick in the belly of a small green frog on a half-sunk log in the middle of the bog./ And the frog got a little bit BIGGER.

Both use -og words, but one uses rich language, complex rhythm and meter, playful rhyme, and has great illustrations to accompany the action. With the phonics reader, the child may master -og words, but s/he isn’t on the edge of their seat wondering what the hog will do next. Notice, too, the other things present in the authentic text: comparative words (bigger) sight words (one, the, a), the ability to predict what might happen next, -ick words (tick, stick, flicks), great descriptive language (creeps, half-sunk, flicks). It’s just richer and more layered than the phonics text. Kids will master -og words and increase their vocabulary.

Both use -og words, but one uses rich language, complex rhythm and meter, playful rhyme, and has great illustrations to accompany the action. With the phonics reader, the child may master -og words, but s/he isn’t on the edge of their seat wondering what the hog will do next. Notice, too, the other things present in the authentic text: comparative words (bigger) sight words (one, the, a), the ability to predict what might happen next, -ick words (tick, stick, flicks), great descriptive language (creeps, half-sunk, flicks). It’s just richer and more layered than the phonics text. Kids will master -og words and increase their vocabulary.

Worse even than that, some states like Georgia are constricting what programs districts can use. This is really problematic — constricting teachers to one of a tiny handful of programs (Georgia lets them choose from 3, and there’s no way of knowing whether they’re the best available) means teachers can’t select the best tool to help a child learn — they can only choose from a tiny pool of options which may or may not address their students’ needs. Their ability to deploy their own creativity and professional skill as educators is likewise constrained.

In a very real sense, balanced literacy was a dramatic swing away from older phonics programs that also threw a baby out with the bathwater — in that case, the baby was direct phonics instruction. Here’s hoping that districts — and state legislatures — see sense and stop this current pendulum swing before it goes too far and we lose some of the best features of balanced literacy in the process. Both are necessary to help kids become good readers.

*The best known of these are Fountas and Pinnell and Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study, but there are many who jumped on this bandwagon.

**I feel bound to note here that I’ve seen balanced literacy leveled readers that are also stilted, irrelevant, poorly bound, and lacking decent artwork. I think this is a feature of trying to write for a specific academic purpose rather than trying to tell a good story and of course, writing to fulfill the demands of a program or a grade level rather than to tell an entertaining story to kids. In general, though, balanced literacy literature is a cut above phonics-based texts.

***Early and frequent language exposure — especially written language — may have a lot to do with this. To some extent it helps explain why some kids pick up reading easily and others don’t, why children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds sometimes learn to read more slowly, and why ELLs may struggle to pick up reading in their new language, but it doesn’t explain everything.