A public charter school in Utah received requests from parents for their children to opt out of the Black History Month programing that the school traditionally uses in the month of February. After that story made national news, the school reported that the parents had reversed course and the program would continue with all students participating. You can read about it here. This was one school, K-9, with about 600 students, but it highlights a larger problem with Black History Month programming. Below are 5 reasons we need to better integrate Black history (and Latinx, and Native American, and Asian-American) throughout the school year.

A public charter school in Utah received requests from parents for their children to opt out of the Black History Month programing that the school traditionally uses in the month of February. After that story made national news, the school reported that the parents had reversed course and the program would continue with all students participating. You can read about it here. This was one school, K-9, with about 600 students, but it highlights a larger problem with Black History Month programming. Below are 5 reasons we need to better integrate Black history (and Latinx, and Native American, and Asian-American) throughout the school year.

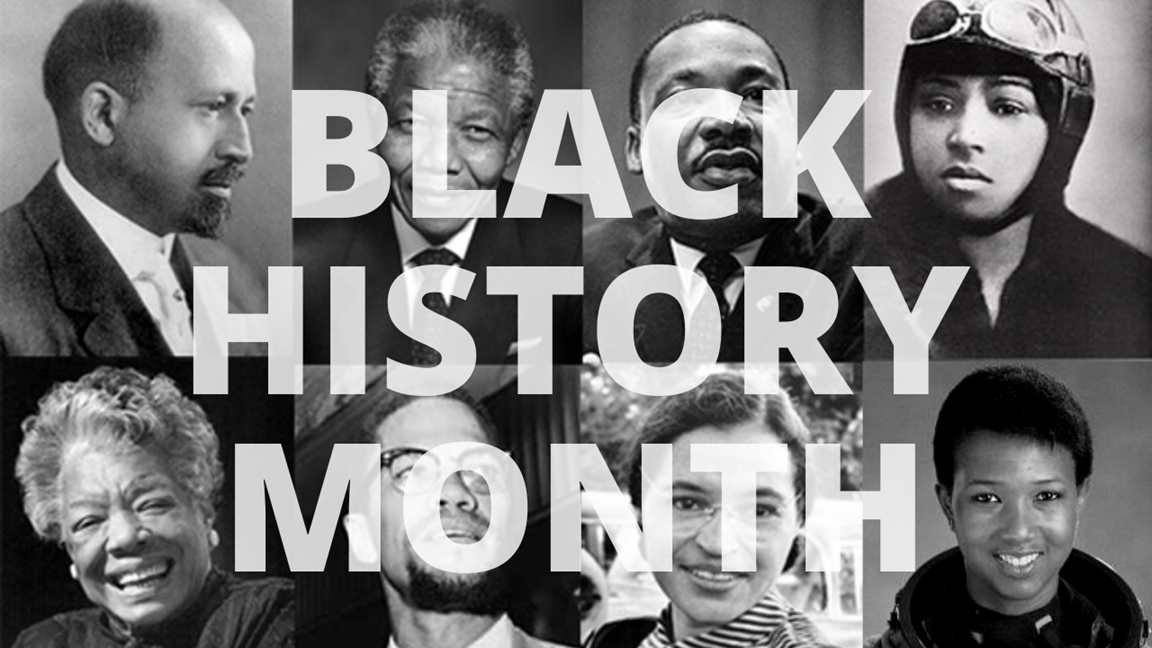

- Designating a single month to the history of a major group tends to constrain the history of that group to a handful of easily recognizable figures. Analysis of student work artifacts from dozens of school districts comprising more than a hundred schools over the last 7 years shows that Black History Month tends to focus on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., George Washington Carver, Rosa Parks, Barack Obama, Frederick Douglas, Harriet Tubman, and Ruby Bridges (mainly in elementary). There might be a smattering of other figures, but the bulk of the focus is on these individuals, who are mainly men. [Update: the above assertion was from CMSi’s experience with student artifacts across a wide variety of systems but I recently ran across research that confirms this practice: King, L.J. & Brown, K (2014). Once a year to be Black: Fighting against typical Black History Month pedagogies] A brief Google search of Black History, however, turns up fascinating people who rarely see the light of day in American Classrooms: Phillis Wheatley, who wrote poetry during the colonial period, despite being enslaved. She was the first published Black writer in the U.S. and only the second woman to be published. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who was a prominent civil rights activist and suffragette in the post Civil War Era. She was also an investigative journalist at a time when women didn’t do this type of work, let alone Black women. She exposed lynchings and other atrocities against people of color and she was a founding member of the NAACP. Bessie Coleman, who was the first Black woman to earn an international pilot’s license and performed breath-taking stunts in airshows around the U.S. and Europe. Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first African-American female doctor in the U.S. Althea Gibson was the first Black woman to compete at Wimbledon — and not only did she compete at a high level, but she won handily in many tournaments. Alice Ball developed the first successful treatment for Leprosy. This just scratches the surface — you can find more Black women in U.S. history here. They deserve to be celebrated, as do many Black men who might not get a lot of class time in a short month. Men like W.E.B. Dubois, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, Daniel Hale Williams, Lonnie Johnson (inventor of the Super Soaker — history doesn’t all have to be heavy) and more. Dig a little on this: you’ll realize very quickly that there’s far more here than can be celebrated in a single month.

- Doing Black History one month a year means a lot of content gets repeated from year to year. Remember I said Black History Month tends to limit focus to a few key figures? Well that limitation isn’t just within a single year, it’s across years, too. Having looked at student work artifacts and school curricula from dozens of school districts across the country, I can tell you that that handful of figures gets a lot of attention over and over again. Kids may do Martin Luther King, Jr. in Kindergarten and grade 1, and grade 2, and then again in grade 3. They may do MLK, Ruby Bridges, and Harriet Tubman at multiple grade levels in elementary school. This is almost certainly a failure to vertically articulate the content from grade level to grade level; teachers don’t know what was covered in 1st grade or what will be covered in 5th. Since it’s just a single month and not integrated into the curriculum in either ELA or Social Studies, there’s no motivation to articulate the content. Teachers just fill in around the curricular edges with whatever they want. If the Black History content were integrated throughout the year, it would be easier to vertically articulate and avoid gaps and overlaps. Some content should be repeated: what kids can understand about MLK in grade 2 is different than hearing his speeches or reading his arguments as a 6th grader.

- It’s not a one-and-done event. The unspoken message is that once February is over, we can put Black History on the shelf for another year because we’ve done our duty. This may be particularly true for the elementary grades, though it can happen in the secondary grades as well. The opposite is true: Black (and Latinx and Native American and Asian-American) History is a rich, important area of study that both needs and deserves year-long attention. Integrating it throughout the ELA and Social Studies curricula gives it both purpose and import.

- We need more than a month to offset the negativity of the rest of history. Without intentional focus on positive achievements, the history of Black Americans (and other non-White Americans) can be subsumed in the rest of “history,” only appearing when the curriculum discusses slavery or the Civil Rights movement (or Indian Removal, or Japanese internment camps, or Chinese exclusion laws). If you are Black and you only see yourself represented in slavery or as the target of racism, this gives a skewed view that can undermine your sense of self worth. Intentionally including Black activists, thinkers, and achievers alongside these uncomfortable topics at every point along the historical timeline can help offset that negativity.

- A single Black History Month is vulnerable to opt-out. A program which is very finite and limited is easy to target for opt-out. Since it’s only one month, parents in Utah evidently had no compunctions about asking to excuse their children from it. In contrast, a program that is integrated in a multitude of ways across content areas conveys a higher degree of priority and is much harder to target because it is more diffuse. We don’t opt-out of things we believe to be critical to our children’s understanding or things that would be almost impossible to remove from the curriculum because they are so interconnected. Understanding the history of our country — our whole country, not just the White bits — is critical to our ability to overcome the discrimination and violence that has plagued the U.S. for so long. Integrating that history everywhere, from PK through grade 12 in as many content areas as possible, is one way we can move the country to a place where all lives are valued and celebrated for their inherent humanity.