This is part 2 of a short series on issues facing teaching and teachers. you can read Part 1 here.

This is part 2 of a short series on issues facing teaching and teachers. you can read Part 1 here.

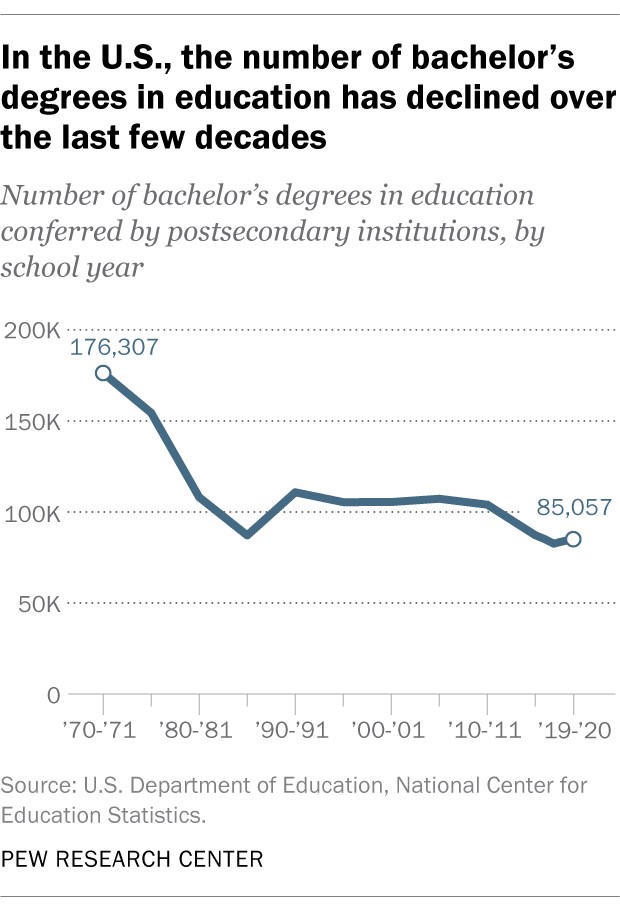

The number of undergraduates electing to become educators has been in a long, slow decline for more than 40 years. This fact has been cited by multiple media outlets and pundits as contributing to the dismal state of education in the U.S. (something I would take issue with, but that’s another post).

According to Pew Research, in 1970-71, one in every five Bachelor’s degrees was in education. It ranked number 1 in a list of the top 10 degrees awarded by undergraduate institutions. By 2011 it had slipped to number 5 on that list. In 2021, it fell to number 10. What’s hard to see on the chart is that there has actually been a slight uptick in the number of education degrees conferred since 2017-18 — about 5% over the last three years shown in the chart. Still, as a proportion of all the Bachelor’s degrees, education ranks fairly low.

What interests me more is why those rates have been falling for so long. I know media outlets often mention the pandemic, the increase in disruptive behavior among school children, the abysmal pay and the culture wars that have made teaching a sort of intellectual minefield. But I think one of these things bears a very close look because if this one thing were addressed and addressed well, many of the other things might diminish in significance. I think you can guess what it is.

Money.

I know, it’s not a huge shock. The fact that teachers are underpaid is pretty well established. But there are some nuances here that might not be fully appreciated. Let’s start with what it costs to get an education degree. According to Forbes magazine, the price to attend a four-year college full-time was $10,231 annually in 1980, including tuition, fees, room and board, and adjusted for inflation. By 2019-20, the total price increased to $28,775, an increase of 180%*. So over the approximate span of time that the number of education degrees has been falling, the cost to get one has been rising sharply. It’s hard to get the data sets to overlap precisely, but from 1996-2021, teacher salaries have been nearly flat. When adjusted for inflation, the average weekly wages of public school teachers increased just $29 from 1996 to 2021 — from $1,319 to $1,348.** And while salary raises occur over the years a teacher remains in the profession, raises are smaller and less frequent than in private businesses, and some districts have a cap on salaries. The average public university student today borrows $32,637 to get their bachelor’s degree. All the other factors notwithstanding, educators’ stagnant salary prospects alone make education degrees unattractive because of the difficulty of paying for said degree.

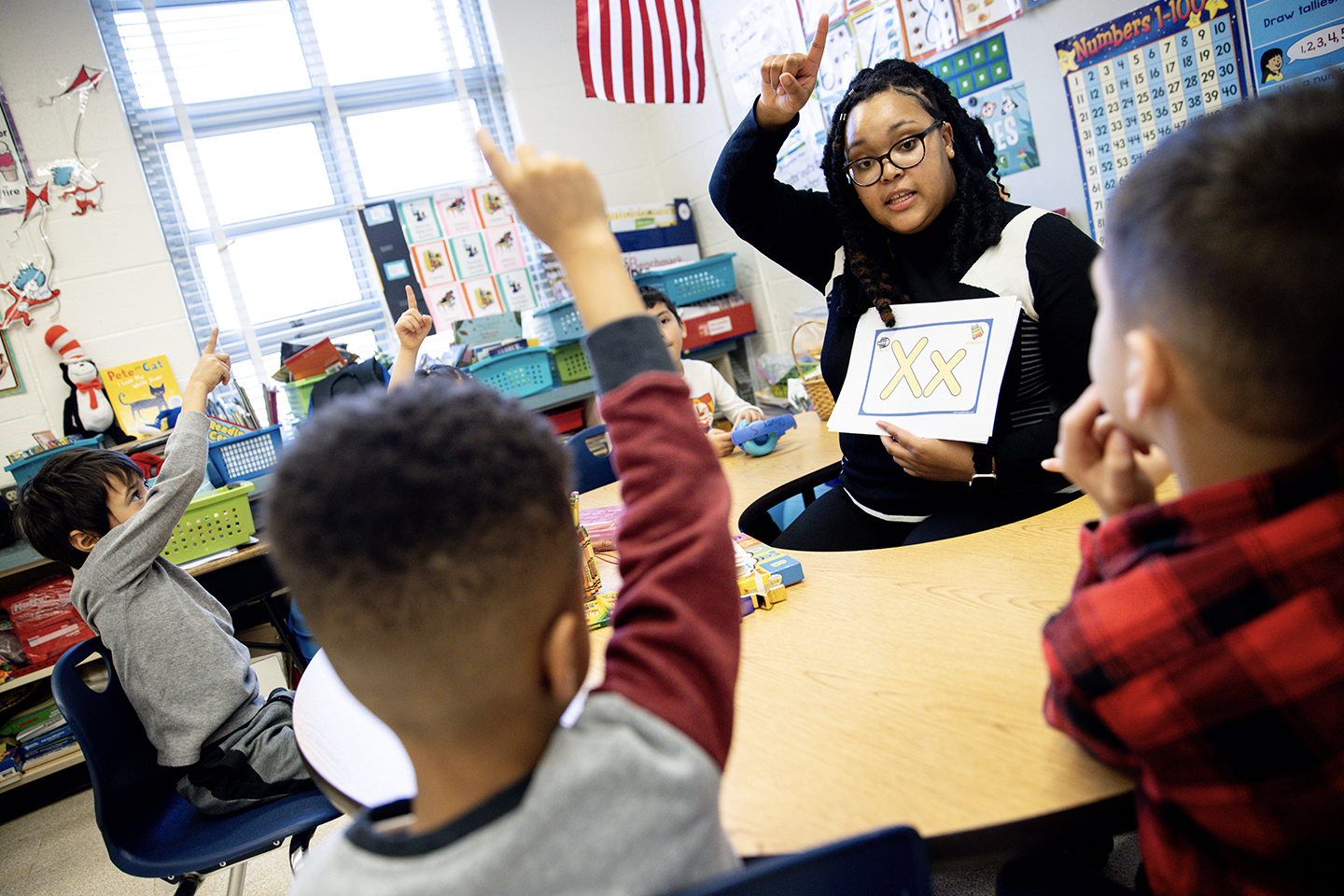

image via EdWeek

This has been cited before, but there’s a significant — unmistakable — gap between what teachers are paid versus other professionals whose degrees required the same level of education and experience. According to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), the teacher pay gap hit a record high in 2022, when teachers were paid 26.4% less than other U.S. professionals with similar education and experience.*** And that was confined only to teachers with bachelor’s degrees or better. The EPI calls this the “teacher pay penalty” or, the penalty you pay in real wages for deciding to be a teacher. The EPI goes on to say,

“The financial penalty that teachers face discourages college students from entering the teaching profession and makes it difficult for school districts to keep current teachers in the classroom. Trends in teacher pay coupled with pandemic challenges may exacerbate annual shortages of regular and substitute teachers.”

In real terms, where teachers were making $1348 per week, other professionals were making $2009. And in case you were going to cite all the benefits teachers get like health insurance and summers off, EPI is two steps ahead: Not only are those benefits not enough to offset the penalty, but even with the benefits, the penalty still grew by 11.5% between 1992-2021. In some states, the relative wage penalty is even higher. The worst is Colorado, whose teachers experience a weekly wage penalty of 35.9%.**** In 28 states, teachers are paid less than 80 cents on the dollar earned by similar college-educated workers in those states.

Y’all.

One would think, in light of the contentious battles waged in school board rooms across the U.S. in the past two years, that Americans value nothing more highly than the education of their children. That care and concern, then, should make attracting the best and the brightest educators out there a priority. And part of attracting good people is paying them well. Instead of higher pay, however, we are seeing requirements to teach dismantled and widespread attempts to attract non-certified, non-degreed people to the classroom. Certainly there should be some non-traditional avenues to entering the teaching profession where a person can both earn a degree and teach at the same time, but when a state allows people with no bachelor’s degree of any kind step into a classroom and take over instruction, it sends a very clear message about what the state thinks about both existing and prospective teachers.

Next time we’re going to look at teacher retention programs across the U.S. to see what steps some districts — and even whole states — are taking to address teacher shortages. Stay tuned.

*There is no consensus here — various sources on the internet give a whole range of percentages. Of the ones I found, Forbes seemed the most reliable.

**A quick Google search will tell you that young workers across fields have not been paid salaries commensurate with the cost of getting their degrees. However, most other fields see both higher and more rapid increases in earnings once they are past those first few years in the workforce, which allows them to recoup some of the disparity. The same is not true for education.

***The first data I found said 23.5% for 2021 and I thought, “wow, that’s bad.” Then I found the data for 2022….

****The lowest wage penalty is in Rhode Island at 3.5%.