image via aspirepublicschools.org

In Part 1, we looked at the legal definitions for equity, as codified by NCLB and ESSA. Today, we’re going to talk about why meeting the goals set forth in both those acts — that all students receive challenging curriculum and the instruction and the resources necessary to master it and that all are adequately prepared for some kind of higher education — requires the unequal distribution of resources. This is glaringly obvious to anyone working in education, particularly public education. Children don’t all show up for Kindergarten at the same point in their background knowledge or in their physical, intellectual or emotional development.

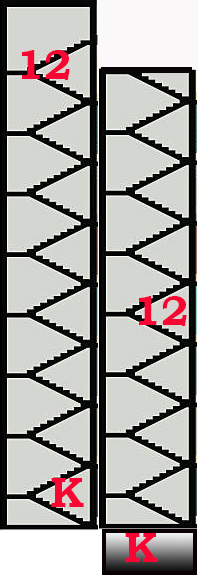

To better understand this, let’s imagine student learning as a tower. All students start at the ground floor lobby (Kindergarten) and move smoothly through the grade levels until they finish high school at the observation deck on the roof (grade 12), ready to start college. Progress in this scenario looks like the image below left.

![]() Students enter Kindergarten, get the available instruction and resources, and progress all the way to grade 12 and the specified destination. Easy peasy, right? But this is in a perfect world. Many schools have more or fewer resources depending on their location (rural or urban versus suburban), which determines their tax base (property values), which in turn determines their funding (how much in terms of resources is actually available). Those variables also affect the quality, experience level, and retention of teachers in the district; with fewer resources often comes less effective (or at least less optimal) instruction. Now we have progress that looks like the image below right:

Students enter Kindergarten, get the available instruction and resources, and progress all the way to grade 12 and the specified destination. Easy peasy, right? But this is in a perfect world. Many schools have more or fewer resources depending on their location (rural or urban versus suburban), which determines their tax base (property values), which in turn determines their funding (how much in terms of resources is actually available). Those variables also affect the quality, experience level, and retention of teachers in the district; with fewer resources often comes less effective (or at least less optimal) instruction. Now we have progress that looks like the image below right:

![]() The unequal resources produce different results; students won’t end up at the observation deck where we want them to be because we don’t have all the resources to get them there. Maybe we’re lacking technology, extra-curriculars, arts programming, up-to-date textbooks, or maybe just enough staff to keep class sizes manageable and assist kids who are struggling. Unfortunately, availability of resources isn’t the end of the discussion. Although Kindergarten is the district’s starting line, many students actually begin far behind or far ahead of that line for a variety of reasons. Some are developmental and governed by the child’s physiology, some have to do with processing disorders like dyslexia, some are behavioral, and some are environmental. Others have to do with individual resources, such as access to one or more years of preschool.

The unequal resources produce different results; students won’t end up at the observation deck where we want them to be because we don’t have all the resources to get them there. Maybe we’re lacking technology, extra-curriculars, arts programming, up-to-date textbooks, or maybe just enough staff to keep class sizes manageable and assist kids who are struggling. Unfortunately, availability of resources isn’t the end of the discussion. Although Kindergarten is the district’s starting line, many students actually begin far behind or far ahead of that line for a variety of reasons. Some are developmental and governed by the child’s physiology, some have to do with processing disorders like dyslexia, some are behavioral, and some are environmental. Others have to do with individual resources, such as access to one or more years of preschool.

Because of this, let’s say that some kids aren’t starting in the ground floor lobby but instead, are starting from the boiler room, one level down. They get the exact same resources as other schools, but their progress looks like the image below left:

![]() Even assuming we have adequate resources, we’re not going to get the same results because of that different starting point. Treating these students exactly like their lobby peers will never get them all the way to the roof. Pretending that it will is to ignore their starting point completely, or worse – to pretend it doesn’t matter. You may be wondering why these kids aren’t just a single floor below where they should be. That’s because lack of learning is a compounding problem; the less a child learns in one grade, the less s/he is able to learn in succeeding grades, especially if their reading comprehension skills are shaky. They aren’t just perpetually behind; they are increasingly behind as they move up the grades.

Even assuming we have adequate resources, we’re not going to get the same results because of that different starting point. Treating these students exactly like their lobby peers will never get them all the way to the roof. Pretending that it will is to ignore their starting point completely, or worse – to pretend it doesn’t matter. You may be wondering why these kids aren’t just a single floor below where they should be. That’s because lack of learning is a compounding problem; the less a child learns in one grade, the less s/he is able to learn in succeeding grades, especially if their reading comprehension skills are shaky. They aren’t just perpetually behind; they are increasingly behind as they move up the grades.

Lastly, and this is in part what ESSA was getting at, some students aren’t even in the same building. What I mean by this is that the program of instruction they are receiving doesn’t look like their wealthier, better funded counterparts. In some cases, the expectations for them are so radically different (think lower) they don’t resemble those of wealthier schools or students at all. If (and this is not a big leap) these different expectations are combined with a starting point farther down and fewer resources, progress now looks like this:

Even with equal resources, these particular students are never going to get to the observation deck by the end of grade 12 because their building doesn’t have an observation deck. Maybe their building is also lacking other things like air conditioning, or on-level textbooks. Maybe their building has high staff turnover because the conditions are so challenging. Maybe their curriculum isn’t challenging or meaningful enough, confined to “the basics” which translates to a lot of low-level, boring activity. Maybe they decide to leave the building before the end of high school because it’s so out of touch with their needs and experiences there seems to be little point in continuing.

Even with equal resources, these particular students are never going to get to the observation deck by the end of grade 12 because their building doesn’t have an observation deck. Maybe their building is also lacking other things like air conditioning, or on-level textbooks. Maybe their building has high staff turnover because the conditions are so challenging. Maybe their curriculum isn’t challenging or meaningful enough, confined to “the basics” which translates to a lot of low-level, boring activity. Maybe they decide to leave the building before the end of high school because it’s so out of touch with their needs and experiences there seems to be little point in continuing.

Equity means we (a) ensure sure everyone is in the same building, and (b) deploy resources to make sure everyone – everyone – gets to the observation deck by the end of grade 12. The first is actually pure equality: everyone has the same opportunity and the same access to that opportunity. The second is a fundamental aspect of equity; inequalities in resource allocation must occur so that equality can be achieved. Is this discrimination? No, and here’s why: these “inequalities” don’t remove critical resources or supports from those who have them already, they only provide additional support and resources for those who need it. If one child needs a wheelchair, we don’t make all kids use wheelchairs in the name of equality. We give wheelchairs to those who need them and not to those who don’t. The ones without chairs don’t miss this resource because it’s not necessary to their ability to get around. In the same way, tutoring, extra classroom aides, acceleration programs, more funding for staffing and interventions, and other increased resources don’t create a lack for those who don’t need them because they don’t need them.

image via yahoo.com

I also want to touch on something that is almost a throwaway in the ESSA text unless you’re looking at indigenous populations specifically – though it does appear in the text relating to all students — and that’s the requirement that children have high quality reading material that is “diverse” and “reflects their interests.” This, too, is an equity issue and falls in the same category as finding yourself in the wrong building. Students of color who are only given books by white authors, with primarily white protagonists, and are only taught a kind of sanitized Euro-centric history of the U.S. that ignores the contributions and experiences (especially the negative experiences) of people of color may feel like education isn’t for or about them. They may begin to feel like their experiences aren’t valid or important – like they themselves aren’t important. They may begin to feel like they don’t belong in the building they are attempting to navigate. This is productive of a kind of cognitive dissonance that is damaging long term. For instruction to be engaging it has to be relevant to the student; books and lessons about people who look like them or share a cultural heritage with them make the material relevant by providing a point of connection. That goes a long way toward increasing engagement. Engagement is a measure of interest, but points of connection relate to both interest and intellectual frameworks for learning. The more points of connection for any student, the better they will learn. If a school doesn’t provide relevant content for kids, engagement can plummet — and disengaged students are not academically successful. There’s been some movement from national organizations on this, which is hopeful. But there are many places actively walking back progress by banning anything related to non-white resources out of a mistaken belief that this constitutes critical race theory. I’ll just repeat what I said in Part 1: this is simply not true. And it’s an untruth that has the potential to negatively affect and restrict learning for a huge segment of the population.

Districts have to do the work of defining equity and equality for their stakeholders in ways that they can understand. Having a handful of analogies helps, but better are clear policies delineating what equity and equality are and the ability to hold the system accountable for achieving both for all students in their care.

If your district would like help improving equity for all students, Contact Us! CMSi has a range of services including full system Equity or Curriculum Audits, deep analysis of student work artifacts for rigor and alignment to high stakes tests, and curriculum design and development. We would love to help you improve learning for kids in your district.