“Equitable treatment means we all end up in the same place.”

– Kamala Harris, Vice President of the United States

Equity is becoming a “trigger” word across the country. EdWeek asserts this is because the way equity is interpreted varies depending on where you are in the U.S. and who you’re talking to. This is concerning, because until very recently, the concept of equity was at least minimally understood. But in the recent wave of anti-Critical Race Theory laws, there has been a persistent attempt to distort the definition of equity – even to assert that equity violates the constitution. The convoluted logic runs like this: providing extra resources for disadvantaged students so they can be brought up to the same level as their advantaged peers (you know – equal) constitutes race-based discrimination because the government must treat people unequally to achieve equal outcomes. This is simply not true. Equity, as a goal, has been codified in more than one federal law. Those laws offer a very useful and specific working definition of equity for American schools. Let’s look at how equity is framed in two recent examples:

No Child Left Behind (NCLB): Enacted in 2002, NCLB began requiring states to report student achievement by gender, racial, and ethnic groups, not just overall achievement. The law specifically required districts and schools to:

- “ensure that all children have a fair, equal, and significant opportunity to obtain a high-quality education and reach, at a minimum, proficiency on challenging State academic achievement standards and state academic assessments.”

- “[meet] the educational needs of low-achieving children in our Nation’s highest-poverty schools, limited English proficient children, migratory children, children with disabilities, Indian children, neglected or delinquent children, and young children in need of reading assistance;”

- ‘‘[close] the achievement gap between high- and low-performing children, especially the achievement gaps between minority and nonminority students, and between disadvantaged children and their more advantaged peers;”

- ‘‘[hold] schools, local educational agencies, and States accountable for improving the academic achievement of all students;”

- ‘‘[distribute and target] resources sufficiently to make a difference to local educational agencies and schools where needs are greatest;”

- “[ensure] the access of children to effective, scientifically based instructional strategies and challenging academic content.”

- “promote equity in education for women and girls who suffer from multiple forms of discrimination based on sex, race, ethnic origin, limited English proficiency, disability, or age.” (all emphasis mine)

Equity – the concept of focusing resources where the need is greatest to ensure that all have the same high-quality opportunities and instruction, and all achieve proficiency – is interwoven throughout the legislation. In fact, it spells out pretty specifically what that equity needs to look like. If we flip it around and ask (as I am fond of doing) what mastery of this act should look like, it’s not hard to formulate a very specific list of criteria, as demonstrated by the emphasized wording above. Central to the act is closing the gaps between subgroups by directing resources to areas of greatest need. That’s equity.

One of the great achievements of NCLB was that by requiring schools to report achievement by groups we were able to see for the first time that some groups were underperforming others, not just in “bad” schools but also in high performing “good” schools. What many may not remember is that between 2002 and 2012, scores nationwide did improve for Black and Latino students, especially in math, but then stagnated after 2012. That situation forced educators to start asking a very important question; what else might be preventing students from improving? (This is the beauty of data; it shows you where you need to ask questions. Without it, we are very literally in the dark). NCLB’s data reporting requirements made it necessary for districts to talk about race and discrimination. Some very good research emerged around this question as we discovered that expectations for those groups might not be the same as for their white peers, that the curriculum was less engaging for them because it didn’t show them people like themselves or talk about their stories and experiences, that overwhelmingly white staff made students of color feel less seen and understood and might be perpetuating some unexamined biases, that teachers didn’t communicate well with economically disadvantaged parents, and that students of color (especially boys) were subjected to more and harsher school discipline.*

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA): Signed into law in 2015 and taking full effect in 2017, ESSA scaled back some of the more intrusive big-government portions of NCLB and gave states more say in what their standards would be and how they would measure them while still requiring equity for all students and targeted intervention for low performing schools and schools where specific subgroups were struggling. Some key requirements:

- “to provide all children significant opportunity to receive a fair, equitable, and high-quality education, and to close educational achievement gaps.’’

- “shall address the learning needs of all students, including children with disabilities, English learners, and gifted and talented students.”

- “help all students develop the skills essential for learning readiness and academic success;”

- ‘‘makes available and uses diverse, high-quality print materials that reflect the reading and development levels, and interests, of children.”

- “culturally based education programs, such as— ‘‘(I) programs of study and other instruction in Alaska Native [and also Native American and Native Hawaiian] history and ways of living to share the rich and diverse cultures of [indigenous peoples].”

- “Each State, in the plan it files under subsection (a), shall provide an assurance that the State has adopted challenging academic content standards and… the standards required by subparagraph (A) shall— (i) apply to all public schools and public school students in the State; and ‘‘(ii) with respect to academic achievement standards, include the same knowledge, skills, and levels of achievement expected of all public school students in the State.” and

- “ALIGNMENT.— ‘‘Each State shall demonstrate that the challenging State academic standards are aligned with entrance requirements for credit-bearing coursework in the system of public higher education in the State and relevant State career and technical education standards” (all emphasis mine).

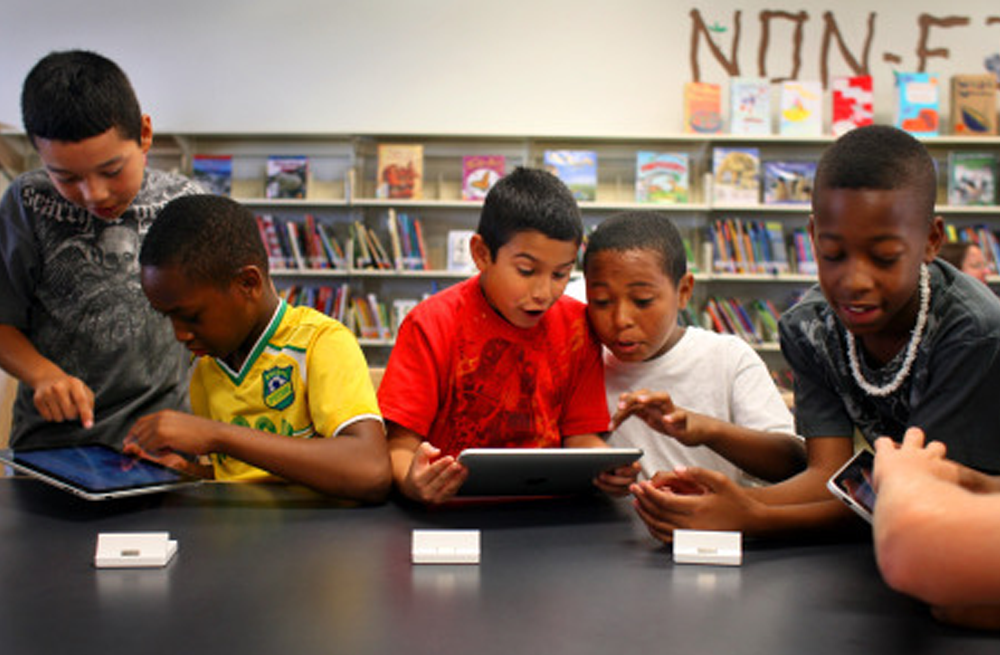

image via lapen.org

In some ways, ESSA reiterates the goals of NCLB but removes the testing component, allowing states to both define what skills students will learn and develop assessments to measure learning of those skills. The overarching directive, again, is to close the gaps between subgroups so that all children can be successful. However, ESSA requires that all children be taught the same challenging academic standards – something that was not required under NCLB. Additionally, those challenging standards must be aligned with entrance requirements for higher education and technical programs – meaning all students must receive instruction that prepares them for college or advanced technical instruction. There are also specific protections for indigenous populations, students with disabilities, English Language Learners, and groups that are not achieving as highly as others, including a requirement for students to have “diverse” reading resources that appeal to their interests and experiences. In this way, ESSA attempted to get at the causal factors for stagnant improvement for children of color identified in research after 2012.

So the goal in both of these pieces of legislation is to get all students to the same high level by the end of grade 12, and ESSA explicitly requires educational programs to prepare all students for higher education. This is the endpoint of equity: all students at the same high level of achievement.

Anyone who has worked in public education knows that to meet this goal requires the unequal distribution of resources because children are not machines; they don’t all show up for Kindergarten at the same point in their knowledge or their physical, intellectual or emotional development. In Part 2, we’re going to examine how this all plays out in the real world.

* This is just a flying overview of what’s available in the research. I could have linked dozens of articles for every topic listed. This is not one person’s opinion; it’s hard science.