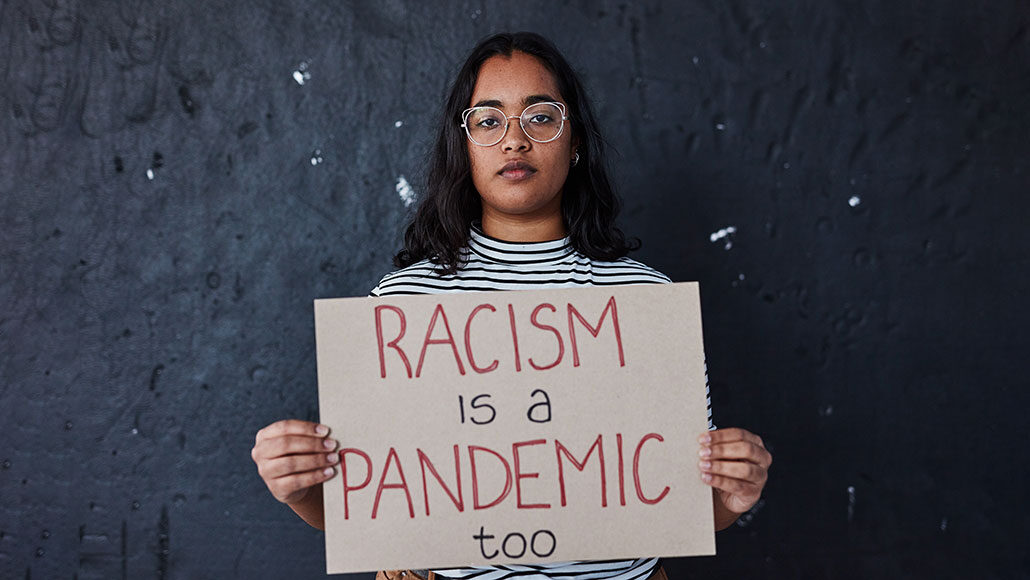

image via sciencenewsforstudents.org

Last post, we talked about Critical Race Theory as a graduate-level framework (lens) that arose during the 1970s among legal scholars as a way of looking at institutions, legislation, and practices to determine if they (not individuals) were perpetuating racism. Like any other critical lens, Critical Race Theory is a way of focusing on a particular perspective for analysis, and also like any other lens, that analysis requires evidentiary support for conclusions. In this post, we’re going to look at why the ability to use critical lenses is desirable for students and why banning Critical Race Theory isn’t necessarily going to have the effect some legislators think it will.

Lenses are, at their core, higher order thinking skills. They require us to examine literature, non-fiction pieces, and historical events from a variety of perspectives. A massive, complex topic like the Civil War can (and should) be examined through multiple lenses — Feminism, Critical Race Theory, Social-cultural, and so on. Lenses also require that we collect and deploy data to support our analysis and that process requires interpretation, organization, and prioritization, as well as the construction of arguments to demonstrate the veracity of our analysis. All of this should culminate in a discussion, or a speech, or an essay of some sort; these last two move the thinking required to the highest level where all the parts are fused into a new whole. Under the old Bloom’s Taxonomy we used to call this Synthesis; under New Bloom’s we call it Creating and it’s the pinnacle of thinking skills, requiring all the other thinking skills and more to achieve. When cognitive demand is at the appropriate level, it’s highly engaging for students, so this type of mental challenge leads to better overall engagement and better retention of the content. It’s a Win-Win-Win.

Critical Race Theory, though, has been banned in K-12 schools by nearly half of U.S. states because it’s been deemed divisive and (say critics) may make white students uncomfortable. But since Critical Race Theory is a lens and not a curriculum, these legislators have failed to note that lenses don’t change facts. Here are a few inconvenient and potentially uncomfortable truths that are unaffected by a ban on Critical Race Theory:

- European settlers actively exterminated indigenous people through warfare, often deliberately murdering women, children, and the elderly.

- Of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, a majority were slave owners. At least 12 U.S. presidents were slave owners; 8 held slaves while in office. Four of the signers were, or later became, abolitionists. George Washington freed his slaves in his will of 1799, but also pursued an escaped slave of his wife’s for the remaining three years of his life.

- The U.S. government entered into and then broke or violated more than 350 treaties with Native American tribes. The U.S. government is still attempting to break treaties with some tribes even as some states attempt to honor treaty promises.

- From 1882-1943, Chinese people were prohibited from immigrating to the U.S. Chinese people already in the U.S. were subject to rules, such as carrying identification papers. Failure to show proper papers resulted in deportation. Those already in the U.S. were barred from returning to the U.S. if they left to visit family in China.

- In 1921, white citizens, some deputized and armed by city officials, destroyed the prosperous Black neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa Oklahoma, razing homes and businesses to the ground over a 35-block area. Ten thousand Black people were made homeless and collectively suffered more than $2 million in property and real estate damage (equivalent to $39 million in 2021). At least 39 people died, though some estimates go as high as 300.

- During the Great Depression, the United States forcibly removed up to 2 million people of Mexican descent from the country—up to 60 percent of whom were American citizens. This was over fears that they would take white jobs.

- Missouri entered the Union in 1821 as a slave state. In 1847, Missouri banned the education of Black people (and here you can plug in a lot of other states and similar laws).

- George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer who knelt on his neck for more than 9 minutes after arresting him on suspicion of having passed a counterfeit $20 bill, a crime for which the maximum penalty is up to 1 year in jail and up to a $3000 fine. Mr. Floyd was not resisting and told the officer he couldn’t breathe several times.

I could go on and on. Nothing in the above list is affected by Critical Race Theory. Lenses like CRT only come into play when we need to interpret how a particular institution or policy or practice may affect people differently because of their race. Redlining is a fact, but interpreting all the effects of redlining on people of color requires a lens and conclusions must be supported with data.

A lot is made of the idea that CRT leads to white shaming and white guilt and promotes division rather than unity. While the potential for this might be there, there is a separate danger in not explicitly examining discrimination: the danger of racism continuing to proliferate to the detriment of everyone. A recent episode of Freakonomics interviewed Kilian Huber, a German professor of economics, who discussed why Germany has embraced educating its students on the holocaust and the role the Nazis and the German public played in it. His answer is revealing:

“I think that it’s still important to try and not only treat it as something that’s in the history books, but try and live with the history, wrestle with it, try and make it come alive in all its horrible form. You learn about a lot of the parallels that appear between Nazi Germany discrimination and modern discrimination. And perhaps you can contribute to preventing those horrendous types of discrimination in the future.“

There’s also often a lot of distress over facts that challenge long-held beliefs about our “founding fathers” or other aspects of colonization that are deemed sacrosanct. But remember, these are facts, not CRT. I would argue that giving kids the full picture makes these characters and events more interesting, more relatable, than maintaining them as icons on a pedestal. Certainly it is productive of higher-order thought — How do we reconcile Washington’s feelings with his actions surrounding slavery? What might it mean that Jefferson wrote a section of the Declaration of Independence (later cut) calling slavery an evil foisted on the colonies by the British? How do we interpret the fact that he legally freed 2 of his enslaved children but continued to enslave the other 2 until his death and did not free their mother even then? These are rich, nuanced, interesting areas of discussion for kids.

CRT was meant to analyze institutions, not to make individual people feel bad. A lot of its impact rests on how it’s carried out in schools. I would argue that done correctly and with sensitivity CRT could lead to evolutions and revolutions in public policy, institutional protocols, how legislation is framed and enacted, how our public services are deployed and managed, and how public education is funded. Note that all these effects are very high level — policy, funding, legislation — not in individual classrooms. The end goal is for all people to be respected and valued, with no legal, systemic, or institutional bars to their success.

This is entirely compatible with what we want in education — for all kids to learn, but also for all kids to be able to learn with nothing hindering their ability to achieve. No policy or practice in the school district should be a bar to student success. We want them using higher order thinking, engaging with content, and becoming independent learners with a sense of their own agency. In many school districts we see vision statements that mention students being global citizens, with underlying assumptions of cooperation and even activism — using their agency to improve things in the community and the wider world. Critical Race Theory offers scope for that as well by helping students analyze where change needs to occur.

Before we reject CRT out of hand, we need to educate ourselves, to know what we’re actually talking about (as opposed to what’s been blown out of all proportion by politicians and partisan media). To that end, here are a few resources:

Here’s a basic run-down on Critical Race Theory — what it is, and why it’s under attack.

Here’s an excellent article on the history of Critical Race Theory and how it’s been warped by opponents into something it’s not.

Read about all the new anti-CRT legislation, including a linked list of new laws and bills which are pending in various states.

How people of color feel about the CRT debate.

Listen to a series of podcasts about Critical Race Theory from Ed Trust. The link shows the full list; podcasts are available for download wherever you get your podcasts. I can’t overstate how good these podcasts are: they offer a variety of perspectives from educators and students and my key takeaway here was that while states can ban CRT, students are completely aware of this gaslighting and are not having it.

Read a scholarly article on CRT. (sorry; this one’s behind a paywall)

Read a historical perspective on CRT that traces its journey from critical lens to political hot button.

Read a short article showing both sides of the CRT argument.

And one last thing: Critical Race Theory is almost always shortened to CRT and that’s given rise to a concerning problem. There’s another CRT out there — Culturally Responsive Teaching — and the two terms are being confused and conflated though they are not the same at all. Critical Race Theory is a lens for looking at literature, systems, institutions, and practices; Culturally Responsive Teaching is a pedagogical practice where teachers and schools intentionally create classroom environments that promote engagement for students of color by “using the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective for them.” (Geneva Gay, 2010). This includes things like offering a LatinX Heritage course, or ensuring your classroom library has lots of books by and about people of color, or intentionally moving beyond Black History Month or MLK Jr. Day to study and celebrate people of color across the curriculum all year long. These are pedagogical choices that are proven to increase achievement for students of color and they do not harm or detract from the learning of white students. Culturally Responsive Teaching fulfills the mandate in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) which requires districts to focus on equity for their students and must be continued as a matter of federal law. We need to take great care how we toss around these acronyms so that districts can continue this important work.