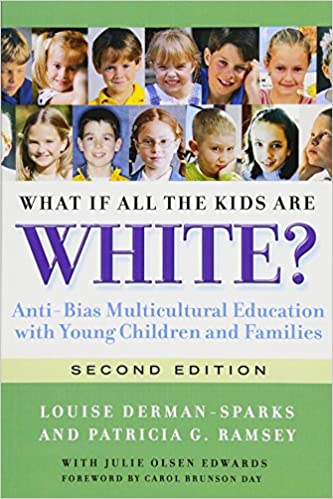

I promised a series on books I’ve been reading to help inform our recommendations for Equity practices and to deepen our understanding of equity pedagogy. Each of the books in the series (4 in all) approaches equity pedagogy from a different perspective, but all the books have a number of through lines in common. They are: Identity Formation, Culture, Agency, Content Connection, and Critical Thinking. Today we’re looking at book number 1: What if All the Kids Are White? Anti-Bias Multicultural Education with Young Children and Families by Louise Derman-Sparks and Patricia Ramsey.

I promised a series on books I’ve been reading to help inform our recommendations for Equity practices and to deepen our understanding of equity pedagogy. Each of the books in the series (4 in all) approaches equity pedagogy from a different perspective, but all the books have a number of through lines in common. They are: Identity Formation, Culture, Agency, Content Connection, and Critical Thinking. Today we’re looking at book number 1: What if All the Kids Are White? Anti-Bias Multicultural Education with Young Children and Families by Louise Derman-Sparks and Patricia Ramsey.

This is a book targeted at early childhood education teachers and programs but it has wider applications and implications for elementary programs. I can’t overstate how profound many of the conclusions here are, perhaps none more so than the need for anti-bias instruction to begin with young children and the need for authentic identity formation.

The book begins with a question that many parents and educators ask: why do we need anti-bias pedagogy if all our kids are white? The authors demonstrate in excruciating detail the state of racism and discrimination in the U.S. and the ways in which even very young children absorb and enact attitudes about race and racial superiority. This is a sharp rebuttal to the assertions that 1) we are a post-racial society, and 2) children don’t “see” race because they are naturally innocent of bias. Plenty of evidence — and it’s old research — demonstrates that children do see race and they begin enacting bias very early (preschool) through their behavior and speech. Even in the absence of other ethnicities, children express ideas and opinions that reflect bias.

The problem with these biases (beyond the obvious) is that without direct instruction children may form identities around beliefs of racial superiority, social standing and/or physical attributes, or economic power and possessions. All of these are detrimental to the child long-term — a belief in one’s own racial superiority can lead to unrealistic fears about other groups, a sense of entitlement, perceptions of people and situations that are driven by stereotypes, and guilt, shame, and/or discomfort when dealing with other groups, especially if the child has witnessed or sanctioned discrimination. The authors also offer sobering research on how an identity formed around economic power and possessions can lead to lower levels of happiness, increased risk of drug and alcohol abuse, and less healthy family relationships. Social standing (closely tied to economic power) and physical attributes (attractiveness, height, weight, hair or eye color, etc.) make for an unstable platform of identity because they invite constant comparison with external measures; if they decline (or the child encounters someone with more or better attributes), self-esteem declines as well.

image via activekids.org

Far better and healthier is identity built on family history and culture, interests, and personal abilities. These highlight and honor diversity that is not rooted in race and focus on each child’s uniqueness without making that uniqueness positional in any way. Interests and abilities are not inherent or fixed; they can be developed and/or change over time. If they go away, other interests and abilities take their place. There are many arenas here for children to explore and find success and satisfaction and all of that is within their control – -they have agency in defining their own identity.

This book is meaty; there’s a lot to unpack and apply in public schools. Of particular value are the case studies from a pair of early childhood programs, one with a mix of ethnicities and cultures and one mostly white, but also take note of the following:

- How early children enact preferences for a specific race;

- How and when white children learn to evaluate their audience when expressing attitudes of racial superiority;

- What happens to non-white students if attitudes about racial superiority are allowed to proliferate in a classroom setting;

- Teachers’ responses to parental complaints and concerns, especially how they encouraged buy-in with the anti-bias pedagogy and how they addressed concerns from culturally diverse and white parents;

- How teachers respond in the pedagogy to what they are seeing in children’s actions and speech;

- Teachers’ creative approaches to anti-bias instruction through engaging, hands-on activities that are relevant to the students;

- The way that teachers and the program enable children to enact solutions to discrimination and address inequities in their world.

Two big takeaways here:

- Start Early. Problems are always smaller and easier to deal with if you catch them early and education is no different. As I read this book, the saying “Begin as you mean to go on” kept floating through my head. If we want equity and we want to honor and value diversity, how much better (and easier) is it to begin with the youngest among us? How much better to lay a foundation of equity and mutual respect, to help children find and celebrate their own uniqueness that doesn’t rely on pushing someone else down? So many equity practices in later grades would operate better, find more fertile ground, if we built a foundation of authentic identity, communicated respect for diversity, and empowered kids to remedy the unfairnesses they see around them right out of the educational gate. This book could be critically important not just in shaping Pre-K programs, but also in informing Kindergarten and primary (and even upper elementary) curricula.

- Hire Well. This type of program requires sharp observation and analysis, creative solutions to issues, follow up to be sure interventions are working, and people skills for miles. Additionally, teachers’ own philosophy of education needs to align closely to the vision of the program. In a program like this, early childhood educators could be the lynchpin for the rest of the district’s anti-bias/equity programing. Making sure the best and the brightest are hired to fill these positions is critically important.

Though I freely admit that the first part of the book detailing the continued presence and occurrence of racism in the U.S. is disturbing and disheartening, the book is hopeful overall. The commitment and creativity of the teachers and the solid recommendations for dealing with the inevitable push-back anti-bias programs get were encouraging. Beyond the practical information, where this book really shines is in how it crystalizes the vision for anti-bias pedagogy. What if All the Kids Are White? is a good starting point for districts as they seek to build their vision of what an inclusive, diverse, and equitable system could and should look like.