A story:

A story:

Back in the late ’90s, a colleague of mine was teaching a World Literature class and had included modern literature from the Balkans. She asked some Bosnian immigrant students who were all 15-18 years old to serve on a panel to help her students have some perspective on the literature. All the kids had fled Bosnia with their families at relatively young ages and all had been in the U.S. for at least 5 years. On the day of the panel, her students had prepared questions about the conflict and she invited the panelists to begin sharing their memories. As the panelists began to speak, they grew more and more agitated. Many began to weep, several uncontrollably. One hyperventilated. The entire panel fell apart in chaos while the stunned World Lit students looked on.

So what happened? If you read this space at all, you know that what happened here was that the Bosnian students were reliving the trauma of the war. But rather than re-hash trauma, let’s go in a different direction and talk about a fundamental mistake this situation illustrates: What might be an intellectual exercise to one person, may open a door on pain and loss for another.

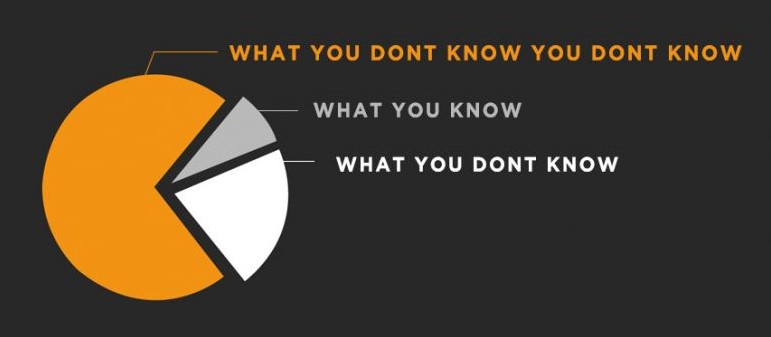

In hindsight, it seems obvious that asking kids to talk about their experiences during a war might go sideways, but in truth, the teacher didn’t know what she didn’t know: that the kids had suffered profound trauma as a result of the war. They seemed normal, acclimated, and so on, but below the surface was a well of lived experience that no casual observer was aware of . Unfortunately, BIPOC are subjected to these kinds of situations all the time with little understanding of how they might be impacted emotionally, either in how the situation is framed, or how a white teacher or administrator responds to them.

Some dodgy scenarios:

- BIPOC staff are asked to “explain equity” for White staff.

- BIPOC staff or students are asked to share their experiences with racism and discrimination with a group without consideration of how those experiences might have traumatized them.

- BIPOC staff or parents raise an objection or concern about a facet of the curriculum that is discriminatory or racist and are told they are “too sensitive” or that they should just “get over it.”

- BIPOC staff or parents or students report racism or discrimination and are ignored.

- Having a staff discussion about discrimination/racism/equity during which White educators express their beliefs that these things aren’t really a problem or are overblown, or in which they complain about “one more thing we can’t say/do” as BIPOC staff look on.

- A class holds a debate over some issue of discrimination such as racially-motivated shootings by law enforcement, or the School-to-Prison Pipeline. This debate occurs either with or in front of students of color, calmly arguing that there’s no discrimination in law enforcement or other arguments designed to discount the experiences of POC.

- A teacher leads a class in a discussion of the Gilded Age in US History (late 1800s) in which they learn about the Dawes Severalty Act and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Both of these acts are characterized as beneficial for assimilation into White European culture (Dawes Act) or for White workers rights (CEA). No perspective from POC is offered or discussed.

- School resources such as worksheets and textbooks that denigrate, minimize, or ignore people of color or only include them in negative or stereotypical ways. Even school informational materials on programs can have discriminatory overtones. Just yesterday I ran across a series of stock photos from a major stock photo supplier depicting a small, blond, blue-eyed (and frankly angelic) boy being bullied by two much larger, brown-skinned boys, one of whom was clearly African American. Depicting the bullies as large and brown and the victim as small and white plays into a host of fear-mongering narratives and negative stereotypes of black and brown boys.

What we haven’t been good at — and I’m looking at us, fellow White people — is thinking about the potential impact of lessons, policies, discussions, activities, responses, and even offhand comments may have on people who have experienced racism or discrimination and accepting that negative reactions to those things are completely legitimate and need to be honored. Just as my colleague didn’t realize the trauma her panel would expose for the Bosnian students, so too we fail to “know what we don’t know” about racism and discrimination: namely, how another person’s lived experiences differ from our own and how their responses to a variety of situations may differ from ours and how we need to validate and affirm that for our students of color.

Here’s a great example of Knowing What We Don’t Know: Lois Beardslee writes in the February 2021 issue of the Kappan about her experiences as a Native American educator and her attempt to get a White teacher to rethink her use of the game Hangman in her classroom. Her assertion that hangman is a graphic representation of lynching and a part of the silent, implicit curriculum that normalizes this type of violence and death was eye opening, as were her experiences with racism well to the north of the Mason-Dixon line. Go read H_ngm_n: What One Says, and Doesn’t Say, to White Educators. It is a powerful reminder that however much we think we know about the lived experiences of People of Color in the U.S., we are still woefully ignorant. We need to err on the side of believing, err on the side of respect, err on the side of protecting our BIPOC students and staff from further trauma.

We have to do better.