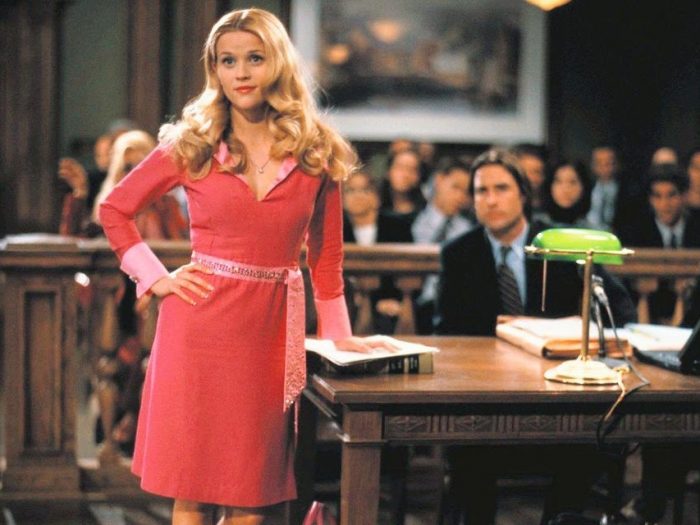

Remember Elle? The fashion-obsessed sorority girl that follows her ex-boyfriend (somewhat improbably) to Harvard Law School and despite her non-traditional background manages to win a highly publicized murder trial, all while wearing her defining hot pink dress? Hollywood fantasy, right?

Remember Elle? The fashion-obsessed sorority girl that follows her ex-boyfriend (somewhat improbably) to Harvard Law School and despite her non-traditional background manages to win a highly publicized murder trial, all while wearing her defining hot pink dress? Hollywood fantasy, right?

Maybe not. Or at least, not entirely.

In Episode 2 of Season 4 of Revisionist History, Malcolm Gladwell examines what he calls the “daisy chain” of the LSAT-Law School-Law Firm pipeline: the idea that the best law schools choose those students with the best LSAT scores, and then the most prestigious law firms choose students from the best law schools. This, in theory, gives them the candidates who are best suited for the job and most likely to do well. Except that it doesn’t.

There is so much here that is fascinating: how the LSAT vets questions, how even just a small increase in the time limits would skew the perfect bell curve that the LSAT current produces, making it even harder for law schools in that elite top-tier to choose candidates, how Canada’s elite universities operate in complete opposition to American elite schools.

A couple things I want to unpack a bit. First, the LSAT-Law School-Law firm pipeline as predictor of success. Turns out that where a person went to law school is not a reliable predictor of whether they will be successful — or stay — with the firm that hires them. Which means that the whole “daisy chain” is based on fantasy. I don’t think you can extrapolate from that that the LSAT isn’t a great predictor of success, but you can assume that it isn’t the only predictor of success. Gladwell cites a certain type of lawyer — the Rainmaker — that all firms need because they are adept at bringing in business. Research into Rainmakers revealed a high proportion of people who went to law schools the researcher had never heard of or went to night school to complete their law degrees. From that you can extrapolate that their LSAT scores were likely on the low end. And yet without them, firms could not exist. In Legally Blonde, Elle gets into Harvard on the strength of her LSAT scores (and a strategic admissions video of herself in a bikini) but what determines her success as a lawyer is actually her sorority girl background and her knowledge of fashion. The plot’s premise is not actually out of the realm of possibility at all. Intriguing research into what predicts success for lawyers is highly dependent on the individual firm and includes such things as blue-collar work experiences.

For public educators, this idea can be applied to the ACT and SAT, long the gatekeepers of entrance into American colleges and Universities. Get a good — or even perfect — score and you are in like Flynn, guaranteed to succeed in the college of your choice. But research actually shows that there’s only a negligible difference between those who are admitted on the strength of their ACT/SAT performance and those who are admitted solely on the basis of their GPA. And in fact, GPA is a better predictor of success than either the ACT or SAT because a high GPA is indicative of an important skill set: discipline, intellectual curiosity, hard work, the ability to bring something to a high level of skill. None of these are measured by the college entrance exams. How could they be? They all require significant inputs of time, which is something students don’t have when they take those tests. This is perhaps why a growing number of colleges and universities are going to “test-optional” admissions.

Second, in my last post I talked about tortoises and hares and Gladwell uses this metaphor throughout the episode to distinguish between two very different types of students: those who do well on the LSAT because they can process information quickly with only minimal understanding (Hares) and those who are capable of plunging deeply into something and absorbing all its intricate logic and detail (Tortoises). He makes the point that while hares do well on the LSAT, Supreme Court Clerks are always tortoises because their job requires them to master enormously detailed cases full of complex legal arguments. In fact, clerks for the Supreme Court read significantly slower in order to do their job effectively. But, and I think this is key, the law needs both tortoises and hares. There are places where both sets of skills are critically important. The problem with standardized tests is that they’re standardized: one-size-fits-all for the rich diversity of American students.

So why continue with standardized tests like the LSAT? Because it makes it easier for law schools to choose who to admit. Among the top 14 law schools in the country, there are 4,500 spots for new law students each year. Over 53,000 students compete for those spots. Currently, admission is based about 70% on LSAT scores and 30% on undergraduate grades.

So how should schools choose? Gladwell makes the point that in Canada, at least at the undergrad level, they don’t. This may be the most intriguing idea of all: what if we let more people in? What if our elite universities weren’t tiny, like Harvard (6,766 undergrads in 2019 — Princeton is even smaller) but more like University of Toronto, Canada’s crown jewel of higher education, with a decidedly whopping 68,314 undergraduates? What if we just made the schools bigger and treated more students to a high-level secondary education? I guess then it wouldn’t be such a big deal to have gone to Harvard, which might actually be the whole point of going to Harvard, especially since research debunked the idea that a Harvard education automatically confers the ability to earn more over the course of one’s career. I suspect the net effect of increasing enrollment at elite universities would be better educated, more successful people all around. Shouldn’t that be the point?

Listen to Revisionist History Season 4, episode 2 wherever you get your podcasts.